The methods of war have failed

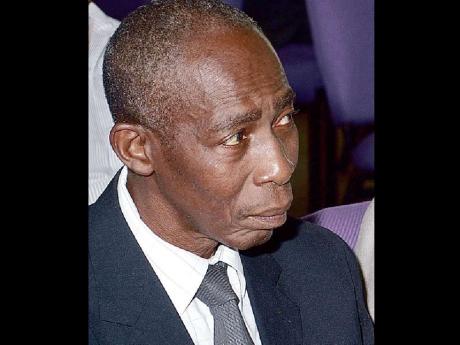

Claude Clarke, Guest Columnist

Reminiscent of his own characterisation of the USA's response to his proposal for a New International Economic Order ("Ronald Reagan killed it with a smile"), Michael Manley met my suggestion that Jamaica disband the Jamaica Defence Force with a devastating smile.

My attraction to the idea of a demilitarised state began after I first visited Costa Rica in the mid-1980s. Its state of order and stability contrasted sharply with Jamaica's lawlessness and disorder. The many Costa Ricans with whom I spoke seemed convinced that their relative tranquillity was the result of their government's decision to constitutionally abolish the military in 1949 and rely on a civilian force to enforce the law and keep the peace. Costa Rica made this decision despite the fact that it was surrounded by highly militarised neighbours.

Doubtless, this demilitarised status was significant in making Costa Rica a beacon of peace in Central America and gave its then president, Oscar Arias Sanchez, the credibility to engineer the peace that ended the Nicaraguan Contra War and win him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1987.

Costa Rica today owes much of its economic success to the valuable social capital that grew out of its orderly environment. It buttressed the economy's competitiveness and provided the reassuring calm so attractive to the owners of capital and their executives.

It has been listed among the 30 most peaceful countries in the world, while Jamaica, with its ever-present military, now ranks 113th. With fewer than nine murders per 100,000, it towers as a crime-free zone when compared to Jamaica, which has more than 50 murders per 100,000. Yet for more than 60 years, Costa Rica has had no military to "enforce order".

I have long held the view that a military force in a small developing island state in the post-World War II geopolitical era is an anachronism. Sitting at the doorstep of the world's most mighty military, jealous of its hegemonic power, Jamaica should have no need to fear any foreign force even thinking of breaching its sovereign territory. In the context of external aggression, our military is, therefore, a solution without a problem.

Where the Jamaican military possesses undoubted overwhelming relevance is in using its power against its own citizens under the rubric of law enforcement. But what Jamaicans must ask is whether an approach to law enforcement that relies so heavily on the tactics of war does not reinforce an environment of violence, rather than encourage a state of peace; reducing the safety of the law abiding, instead of increasing it.

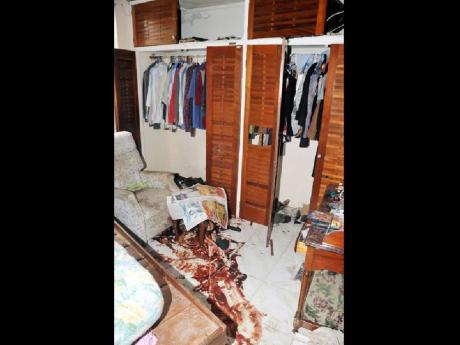

I could never have imagined that the year 2010 would have so tragically brought unassailable evidence of the validity of that belief. In the dead of night, my brother's life was snuffed out by a marauding military that ruthlessly violated his God-given, legal and constitutional right to his privacy, his property and his life.

Murdered by JDF

Keith Clarke's brutal murder by those whom he, along with the rest of society, had paid to protect him was obviously unjustified and indefensible. Yet three long years later, those who sanctioned, planned and executed the savagery that was unleashed on his neighbourhood, his premises and his family, invading his most private sanctuary, his bedroom, have not been made to account for their deeds.

Three years of insistent and persistent effort by the police Bureau of Special Investigations (BSI), the Independent Commission of Investigations (INDECOM), the Office of the Public Defender, and civil society have failed to persuade the Jamaica Defence Force (JDF) to provide a credible explanation as to why it did what it did that fateful night. The military has stood in splendid isolation from both the scrutiny of the State and any obligation to account to its citizens.

How could any person or institution bound by law in a truly democratic society show such contempt for civil authority and the people it is paid to serve? Or is it that the military is beyond the reach of the law and the Constitution?

The army's extraordinary power was haughtily displayed before the Manatt commission of enquiry when the identity of the head of its Intelligence Unit and information he possessed were held to be beyond the jurisdiction of the commission. Yet the heads of the USA's CIA and Britain's MI 5 enjoy no such protection. Everyone knows who they are and they are regularly brought before public bodies to be deposed, exposed and often dressed down. Not so the JDF.

While the Manatt commission tore through the most highly placed and protected personages of the Government, revealing their most closely guarded secrets; the military stood aloft and aloof from its judicial scrutiny.

The public defender, in his report on the Tivoli massacre, lamented his inability to extract a proper accounting for the military's actions in Tivoli Gardens. The BSI fared no better in its efforts to access information in the matter of Keith Clarke's death. The family was filled with hope when, in mid-December 2010, we were told by the head of INDECOM that all that remained for his investigation to be completed was the ballistics report from the government lab and a statement from the military regarding the 'intelligence' that led them to Keith's home. He was promised both within another two weeks.

Still no explanation

The ballistics report was not done for two years. To this day, three full years after the incident, as far as we are aware, no agency of government has received anything from the military to explain why they invaded my brother's home.

The actions of Jamaica's military during those fateful days in May 2010 are not without precedent. Four hundred and thirty-nine black Jamaican men and women were mowed down in Morant Bay by British colonial troops nearly one and a half centuries ago. But while the Morant Bay massacre might have been explained by the unaccountability of colonial power to newly freed slaves, the slaughter of May 2010 was visited on people who were democratically enfranchised and free: people to whom their elected governors are answerable.

When I first entered government in 1989, I was bewildered by what seemed to have been a settled belief that talk of disbanding the JDF was silly. But had I taken the time and trouble to consider the matter, I might have understood then what now seems crystal clear.

The high-handed posture of the JDF at the Manatt commission and the contempt shown to agencies specially empowered by our Parliament, speak eloquently of an institution operating beyond the power of the State. And the revelation that a former prime minister, who headed the military in form, so distrusted it that he preferred to get information on military intelligence from an external source, underscores the point.

Why would a government maintain an armed entity over which it has such tenuous control unless it felt powerless to do anything about it? With no danger of external threat to justify its existence, its reason for being would be no different from that of the colonial forces whose purpose, 150 years ago, was to assuage the colonial masters' fear of the people. However, Government's inability to rein it in is perhaps the result of another fear; that of attracting the displeasure of an armed force whose obedience it may not be able to guarantee.

Costa Rica disbanded its military partly to remove the fear of overthrow of its democratic system of government. But for the people, its government displayed not fear, but respect. Declaring that "the army would be replaced with an army of teachers", it promptly used the money saved by disbanding the military to invest in the people. It now provides largely free education and health services that are recognised as the finest in Latin America. As a result, today it is the productivity of its people that is at the foundation of its economic success.

Jamaica has not had a history of military intervention in politics, but it is dangerous for such a force to be so frequently mobilised to perform the duties of law enforcement; to the point where the government is seen as incapable of maintaining order without it. Lawbreakers are being conditioned to believe that the military is the only institution worthy of their respect or fear.

Some years ago, the chief of defence staff told us that "the JDF must have at its core a war-fighting ethos". Unleashing such a warlike culture on the streets can only inure our society to violence and undermine the authority of the civilian government. These images of war on our streets have contributed in no small way to the chronic ineffectiveness of the normal security apparatus of the State.

The methods of war to which we have grown accustomed have harmed, not benefited, our country. A new era of order and stability could begin if Jamaica were to follow Costa Rica's lead and disband the JDF; or at the very least discontinue its combat role and limit its activities to civilian purposes like search and rescue and dealings with natural disasters.

Claude Clarke is a businessman and former minister of industry. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com.