‘I was telling people I don’t want to live’ - Dad gets last-minute reprieve from UK deportation flight as other families hurt

A Jamaican father taken off a United Kingdom deportation flight just minutes before the plane doors closed last week has spoken about his desperate last-ditch reprieve.

Arthur* was one of 50 Jamaican nationals the UK Home Office had booked on a charter flight that left Stansted airport at 1 a.m. on Wednesday.

Following interventions, 37 people were removed from the flight, but 13 were deported to Kingston as planned.

“The seat belt light had come on. The engine noises had started. The only thing I had with me was my Bible. Then an immigration officer called my name and said, ‘Get up. You’re off the plane’,” Arthur told The Sunday Gleaner.

“That relief I feel, I’m telling you, was unbelievable. It was like someone choking you and then letting go so you can get that breath that you dreamt of breathing.”

The deportations came under the British government’s blanket policy of removing foreign nationals sentenced to more than 12 months in prison. The policy has attracted widespread criticism from activists, legal experts and celebrities, who say it is being implemented in a racist manner and with scant regard to the human rights of individuals and their families.

Karen Doyle from Movement for Justice, the human rights organisation that intervened in Arthur’s case, said, “For the UK government the racist, hostile environment serves a purpose. They have targets to meet. They want to get rid of as many people as possible. This is how the Windrush scandal happened.”

3 DECADES IN ENGLAND

Arthur, who has lived in England for nearly three decades, has five children with his wife of 24 years, as well as two from a previous relationship. After struggling with addiction and a drug conviction, he has turned his life around through rehabilitation. His family depend on him and say that losing him would devastate them.

Since his release from prison in 2014, the threat of deportation has been a constant in Arthur’s life. He is electronically tagged and must report to the immigration and probation authorities three times a week. At his most recent appointment in November, he was told that a plane ticket had been booked to return him to Jamaica. From there, he was taken to a detention centre to await his fate.

“What I’ve felt these last two weeks I wouldn’t wish that on my worst enemy. I was telling people I don’t want to live no more. They want to take me away from my family and that’s all I have,” he said.

Campaigners feel the UK government disproportionately targets Jamaicans, and that chartering mass deportation flights in the context of the ongoing Windrush scandal is fundamentally wrong.

“Arthur is an advert for rehabilitation,” said Doyle. “He’s never reoffended, complied with the reporting restrictions of the Home Office, he’s clearly no risk to anyone. They’re a loving family and he’s an important figure in his kids’ lives. But he’s never been able to get this burden off his back.”

Arthur’s wife, Paula*, is suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder since being attacked at work in January. She is recovering from mental and physical health issues. Arthur is her main carer.

“Without my husband, I’m nothing,” she said. “I have low days and high days. On low days, I don’t come out of the house or answer the door. Arthur is my only caregiver.”

With emotion clear in her voice, Paula described the impact of Arthur’s attempted deportation.

“Everything has crashed,” she said. “I was feeling to take my life and the crisis team had to intervene. Social care are assessing my kids. I told them they just need to release my husband.

“Arthur does the shopping, he cooks, he combs the kids’ hair, drops them at school, picks them up, helps them with their homework. There’s institutional racism going on at the Home Office. They have no empathy whatsoever,” she lamented.

While Arthur remains in the UK for now, others were not so lucky.

A woman who spoke to The Sunday Gleaner on condition of anonymity revealed how her nephew was deported on the late-night flight.

“He said, ‘Aunty, I have to get off the phone. They’re going to take me to the bus.’ He said when he gets to the airport, he’ll turn his phone back on. His phone never went back on.”

Her nephew had applied for asylum in the UK, but had his application rejected.

“He was a nurturing father to his two kids. They’ve now lost a father at a sensitive age. His son is worried he’ll never see his dad again.”

PLEAS IGNORED

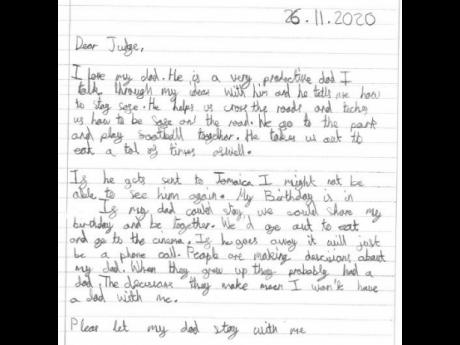

A heartbreaking letter written by his 10-year-old son was shared in a tweet by the organisation, Detention Action. But his pleas to let his dad stay were ignored.

The 13 deportees were held in a hotel upon arrival at Norman Manley International Airport, where they were tested for COVID-19 before being released two days later.

In a letter addressed to Prime Minister Andrew Holness, the rights group Advocacy Matters 4 You urged the Government to support deportees upon their return.

When asked what provisions the UK makes to ensure adequate resettlement in Jamaica, a Home Office spokesperson told The Sunday Gleaner, “We work closely with other countries to ensure that the disembarkation and handover process runs smoothly. Once the individuals disembark, they are under the control of the receiving country’s authority.”

In 2019, the UK pulled funding for the National Organization of Deported Migrants charity, which helps Jamaican deportees reintegrate, just days before announcing funding for Windrush victims.

When asked whether Jamaicans were over-represented in mass deportation cases, compared to citizens of other countries, the Home Office said, “Jamaica makes up just one per cent of return flights. In recent weeks, we have returned 18 people to Romania and 17 to Lithuania.”

In a joint statement, Deputy Prime Minister Horace Chang and Foreign Minister Kamina Johnson Smith said the 13 deportees had “met the criteria for removal set out in the UK Borders Act of 2007,” and went on to say, “We are informed that no Windrush victims or persons eligible for compensation under the Windrush Scheme were included among those removed, and that factors such as the right to family life and issues around trafficking in persons … were taken into account.”

It also noted an agreement reached with the UK government that no one who arrived in the UK before the age of 12 would be removed on the flight.

Arthur, who arrived in 1994 and has lived most of his adult life in England, hopes to spend Christmas with his family rather than in detention. But he remains at risk of deportation and in perpetual fear.

“When you go in and that door slam,” he says of his regular check-ins with immigration authorities, “it’s only God can tell if you’re going to come out. And you face that judgement over and over again.”

*Names changed.