PRISON CELL DISCONNECT

Failed trial highlights gaps in new contraband legislation

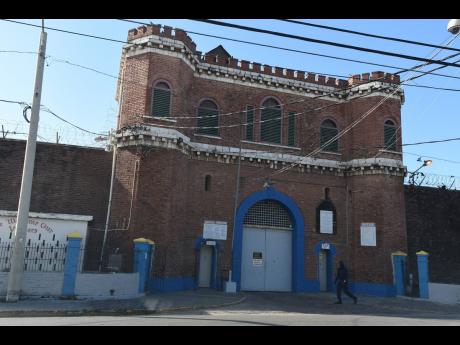

A law enacted nearly three years ago to stem the influx of cell phones in prisons has failed its first test, forcing a prosecutor to end the trial of a prisoner who was purportedly discovered with two mobile devices in his cell at a maximum-security facility.

Adrian Clarke, who is serving a 15-year sentence for a gun attack on a man, was on trial for possession of a prohibited electronic communication device.

He was charged after prison guards claimed, in a report to the police, that they found the two mobile phones – an iPhone and a Samsung – during a search of his cell, along with a Samsung Galaxy Watch and chargers for both phones.

Possession of a cell phone while in custody became a criminal offence after Parliament passed the Corrections (Amendment) Act 2021 amid a spate of violent crimes such as murders and robberies across the country, which police investigators believe were orchestrated from behind bars.

But on September 5, the case against Clarke collapsed in the Kingston and St Andrew Parish Court after the prosecutor, citing the testimony of one of the correctional officers who conducted the search, conceded that proving possession would be difficult.

“The evidence in this case lends itself to the possibility of the defendant not having complete control of the cell,” said the prosecutor, referring to the testimony of the correctional officer that cells are sometimes occupied by more than one prisoner. “This would militate against satisfying the court beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant had possession of the devices. And I am not certain, based on what has been adduced thus far, in addition to the exhibit [device] not being available to the court, that we could mount a successful case.”

Prevalence of offences

The devices were not available to the court because they are still with the police’s Communication Forensic and Cybercrimes Division for analysis, the prosecutor disclosed.

“It is unfortunate because I am aware of the prevalence of offences of this nature and the need for there to be controls,” the prosecutor lamented before indicating, “we offer no further evidence against the defendant”.

Clarke is one of 10 people placed before the courts for breaches of the Corrections (Amendment) Act 2021 between the time the legislation was enacted and the first quarter of this year, according to the Court Administration Division (CAD).

Five pleaded guilty, three cases were dismissed, while one was listed as “inactive”, the CAD told The Sunday Gleaner.

Police spokesperson Senior Superintendent Stephanie Lindsay did not respond to questions submitted by The Sunday Gleaner last Wednesday enquiring whether their statistics accords with those compiled by CAD and what accounts for the small number of cases placed before the courts.

However, one former police investigator explained that it was difficult to file charges “when you find the phone in a lock-up with 10 people”.

“What are you going to do? Charge all 10 a dem?” the ex-investigator questioned, noting that there were “other issues” involved without explaining. “If you catch a man attempting to get the phone into the prison then you can charge him, but if you go into the lock-up and find it, what can you do?”

Phones have long been prized possessions for prisoners.

Entertainer Vybz Kartel has publicly acknowledged, in several interviews since his release from prison, that guards regularly seized cell phones and other devices he used to record songs behind bars.

However, he has not disclosed how he got possession of the devices.

“I came under a lot of pressure … a lot of searches. If they saw me with an iPad, they would seize it. All my recording devices were seized,” he said during an interview with American radio station Hot 97 last month.

Stephan Willis*, a St Andrew man who spent 12 years in prison before he was exonerated of a murder charge, admitted that he lost a total of 52 cell phones.

“So me lose one, so me get back one,” he told The Sunday Gleaner last Thursday.

He, too, declined to discuss how he got possession of the devices.

The Corrections (Amendment) Act 2021 created several new offences, including having access to, use of, or possession of an electronic communication device or computer in a correctional institution; tampering with any electronic communication device or computer by an inmate; and an inmate transmitting, or causing to be transmitted, without authorisation, any data, using an electronic communication device or computer.

It also provides fines of up to $3 million and a three-year prison term for offenders convicted in the parish court. A second or subsequent conviction carries a fine of up to $5 million and up to five years in prison.

The reasoning behind the decision to halt Clarke’s trial is indicative of the challenges prosecutors will face with similar cases, one attorney opined.

“The problem is the inability of both the DCS (Department of Correctional Services) and the JCF (Jamaica Constabulary Force) to provide attribution, basically by saying how inmates come by the phones and how it was introduced into the prisons,” the attorney asserted.

“All of that is of great importance, especially when people stand to lose their liberty. I think the drafters of that legislation need to go back to the drawing board to close the gaps,” the attorney added.

Justice Minister Delroy Chuck directed Sunday Gleaner questions on the matter to the Ministry of National Security. There was no response from the national security ministry up to press time last night.

However, attorney Peter Champagnie, KC, argued that the outcome of Clarke’s case is an indication that the investigation around cell phones found in prison needs to be more thorough.

DNA and fingerprinting evidence

“By that, I mean the employment of DNA and fingerprinting evidence if it’s available … to see if it’s attributable to one individual,” he suggested during an interview with The Sunday Gleaner on Friday.

Eight people, including a seven-year-old child, were killed and nine others suffered gunshot injuries when armed thugs opened fire at a birthday party in Cherry Tree Lane, Four Paths, Clarendon, last month in one of the deadliest mass shootings in Jamaican history, which police investigators believe was “organised” from prison with help from cronies overseas.

Citing police investigators, The Sunday Gleaner reported last month that a recent wave of daytime robberies – resulting in the theft of around $300 million from cash-in-transit teams – was orchestrated by an “alliance” of imprisoned leaders from multiple violent criminal gangs.

In another case, Deryck Azan, a Manchester man who is serving a 17-year sentence for shooting at a police team, was charged in 2021, along with three other men, for the home-invasion killing of four members of a Clarendon family.

*Name changed.