Testimonial of complexity of creativity in Jamaica

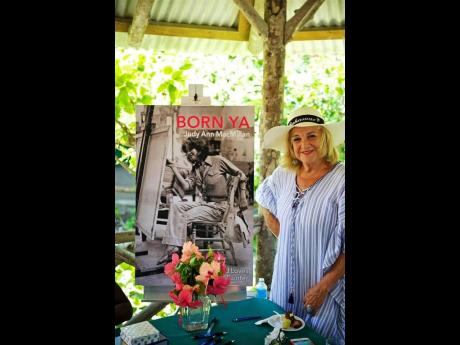

Judy Ann MacMillan’s autobiography Born Ya: The Life and Loves of a Jamaican Painter captures with verve and passion the struggles of a light-skinned Jamaican woman to be a painter in the ‘humid island incubator’ of Jamaica in the latter half of the 20th century. In the process of doing this MacMillan vividly brings to life a Jamaica most of us would never know, rare glimpses into the 40s and 50s, the waning years of empire in a colonial outpost. Later she retails stories of balancing domesticity with the all too masculinized profession of painting in postcolonial Jamaica where the art elite looked down on traditional painting practices such as her own.

MacMillan’s point of view is unusual and rendered with great style and humour. Born Ya is punctuated with insights from an intelligence that not only knows how to translate what she sees into technically superb two-dimensional form but one capable of skewering the provinciality of her country folk with uncanny skill and wit. Of the people of St. Ann, the parish her mother came from, Judy writes: “They never forgot a slight; held on to grudges until death and found the very mildew of St. Ann to be sacrosanct.”

Of the love of her life she says: “Jimmy’s rural ancestors had taken very seriously the Biblical command to go forth and multiply. There were thousands of illegitimate relatives all over the countryside with a striking resemblance to him around the lips and eyebrows.” Her feeling of vindication at being acknowledged by the famous art historian Edward Lucie-Smith is heartfelt and moving: “I felt a part of the big family of painters in my time--part of that community that I was starving for in my jungle.”

The title of the book is taken from the Pluto Shervington song ‘Sweet Jamaica’, one of many capturing the fierce loyalty and love most Jamaicans feel for their country. “But I man on ya, I man born ya, I nah leave fi go America…” And neither does Judy Ann. Some of the most compelling portions of the book are the passages where MacMillan describes her lifelong relationship with art. Some of the least engaging are the ones describing her marriage to an American, father of her son Alexei, and her abortive attempt to be a suburban American wife. Fortunately her sojourn in the US was short and we return to the hustle and bustle of Jamaica where the artist forgets herself completely “and someone deep inside me paints.”

The early chapters where MacMillan describes meeting paradigmatic Jamaican artists such as Carl Abrahams, Albert Huie, Ras Daniel Heartman and Eric Smith, among others, are a treat for anyone interested in Jamaican art history. MacMillan took art lessons from Abrahams at the age of eight and bought her first painting from Huie soon after. She sold her first oil painting at the age of 11 at Hills Gallery on Harbour Street, the only art gallery in the country at the time. Thrilled at the red sticker indicating the painting had been sold Judy Ann was mortified on realizing it was her proud father, Dudley MacMillan, who had bought it.

Dudley G. MacMillan, a self-made man and bon vivant, is brought to life vividly by his daughter. The founder of Jamaica’s first advertising agency, MacMillan Advertising, in 1929, MacMillan was also an impresario who brought many of the top international performing stars in theatre, film and music to Jamaica. Starting as a messenger boy at the Gleaner where he was so appalled by the ads merchants sent the newspaper, Dudley decided to design ads for them himself, convinced he could do a better job. While he thrived in advertising Dudley’s real love was show business and by ingeniously persuading managers of orchestras and musicians from London and New York to make Kingston the first or last stop on their South American tours was able to get star acts such as Nat King Cole, Bill Haley and the Comets, the Berlin Philharmonic and the London Philharmonic to play in Kingston, Jamaica. In between there was a steady stream of strippers and glamour girls from Havana and Judy Ann fondly recalls the almost continuous parties at their home.

Definitely a Daddy’s girl MacMillan deftly captures her mother Vida’s ‘facety’ character as well and describes the ups and downs of her parents’ ‘mismatched’ marriage with humour if not compassion. Volatile and uncompromising Vida was distraught when Jamaica became independent fearing it was ‘the end of the island’. Her legendary impatience and refusal to brook anything contrary to her desires met its match however when Vida encountered a higgler who was just as facety. “My dear woman, ten pounds for a head of lettuce? You must be completely mad!’ said Vida. ‘Eat de money den nuh,’ the higgler laconically replied.

Macmillan describes her mother’s dislike of former prime minister Michael Manley and the panic of the business classes, many of whom left Jamaica during his tenure. While family friends fled Jamaica in terror at what they perceived as the ‘communist threat’ her father took out a large ad in the local papers with a photo of his advertising agency and a headline saying, “We’re staying.” Other laugh out loud moments include a description of the family dogs, one of which, ‘having only ever heard the word ‘outside’ from my mother would come running because he thought it was his name.”

It’s when MacMillan talks about her calling as a painter, the work of an artist who paints directly from life rather than photographs, and all the attendant perils thereof, that the book takes on a different dimension.

“Painting from nature is not relaxing, it’s tense. The mind is speeding on an abstract tightrope of line, tone, colour, drawing, shape, texture and scale, while the hand clumsily, frustratingly tries to keep up.”

Even here the humour is ever present: “…I was not filled with a mad passion to paint in a frenzy all night. Nor did I ever feel like cutting off an ear or anything like that.” Fond of painting street people Macmillan described a session with a beggar named Nana who was “a ferocious devotee of the PNP”.

“Every time she came, I would ask her to say ‘power’ for me and happy to be asked she would go into her performance. She would plant one foot to steady her and shake her entire body up from this pivotal point with the arms rising and shaking to triumphant rays above her head and scream, ‘P-O-W-A-H-H-H!’

A recurrent problem with male models was that they would inevitably be aroused when asked to strip naked and pose for MacMillan who unperturbed would paint away occasionally editing out the huge erections she encountered. The story of one of them, Bap the goat herder, who when invited to model for her told Judy Ann he had once posed for Edna Manley, prompts a mischievous dig at the latter: “In truth, he looked exactly like that statue of Bogle that she did—a short, tough little man –and now I know where she got the idea for the huge machete that he holds down the front of his body.”

Looked down upon

Alas MacMillan’s penchant for painting portraits and landscapes was out of step with the prevailing artistic regime in Jamaica which by the 90s had begun to spurn traditional painting and sculpture for more internationally trendy media such as installation, assemblage, arte povera and conceptual art. MacMillan sums up the situation succinctly. “To be out of fashion in a tiny place that is paranoid about this was to prove an embarrassment to the provincial arbiters.” Representational artists such as Albert Huie and herself were looked down upon by the art establishment. Undaunted MacMillan approached the internationally famous art critic Edward Lucie-Smith to write a critical text for a commemorative book celebrating Huie’s career.

The chapter on MacMillan’s tempestuous affair with Jimmy Jobson, one of those unforgettable characters only Jamaica can produce, is priceless. The chapters on her son, Alexei, and her granddaughters, reveal other sides to this unusual woman who asked for little more than to be allowed to pursue the career of a painter.

Judy Ann’s descriptions are peppered with asides in the Jamaican vernacular by an unseen voice, offstage, snidely commenting on her statements, an innovative way to signal the bilingual, hierarchic nature of life here. So a description of her childhood friends Mary Hanna and Richild Springer (recently deceased in Barbados) as being white and black is interrupted by the italicized observation, “She bringing colour into it now.” Colour is something MacMillan doesn’t shy away from. Describing her father’s early days at The Gleaner she notes that Theodore Sealy (the Gleaner’s first black editor) was hired for a similar job at the same time but whereas her pale-skinned father was paid fifteen shillings a week Sealy, a black youth, was paid only ten. The inevitable comment from the penny section follows: “Fyah! Powah! All dat foolnish-nis soon stap when Black Man Time come.”

There will be the inevitable criticism that this joyous, joyful book represents a narrow elite life and viewpoint. If only more elites and middle class writers would write about their own lives with as much depth and honesty we would all be better off for it. As it is this is an underrepresented, underwritten area with most writers choosing to ventriloquize the ‘masses’, the ‘people’, the ‘folk’ or the so-called proletariat, often unsuccessfully. As it is, Born Ya is a valuable, enriching book, a testament to the incredible complexity and creativity of Jamaicans at all levels of society.