Where’s the art in construction?

Jamaican fine artist Joshua Higgins is concerned about what he perceives as a decline in the local art scene and the glaring lack of an artistic imprint on the current construction boom under way in Kingston and other parts of Jamaica.

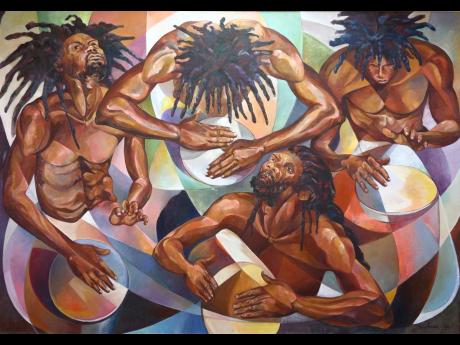

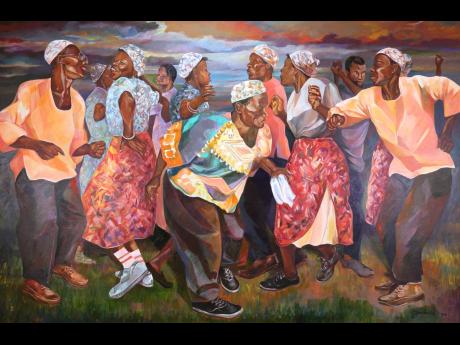

The painter, whose works grace the halls of international institutions around the world, feels that this apparent disinterest in art is contributing to the coarsening of Jamaican sensibilities and the growing alienation manifested in the absence of an aesthetic appeal, especially in urban spaces, for enriching the lives of youth and the general populace.

“Art is important for so many reasons. It livens up the dull, concrete spaces and gives people a deep connection with their emotions like love, beauty, serenity and faith. It can inspire hope and enrich the quality of life of our people,” he says.

Higgins, who spends time between Canada and the United States when not home in Jamaica, is concerned about the dwindling number of art galleries in Kingston, noting that many spaces that make such claims are nothing but “glorified frame studios” rather than true galleries.

He is prepared to be an advocate for a revival of the Jamaican art movement and feels that the Government needs to first recognise the importance of carving out a section of its budget for construction projects to include works of public art that capture “the essence of the Jamaican experience and the sensibilities of our people”.

“Our urban planners and architects must factor art into their decisions,” he states, noting that such arrangements should be legislated if not already so. ”Individuals, corporations, law firms, and banks have led the way in this regard, but it needs to become more entrenched,” he asserts.

Art is a definer of cities

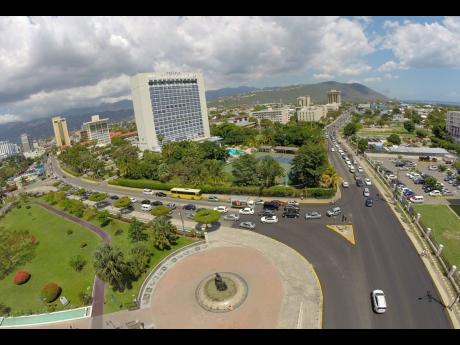

“When people think of cities around the world, invariably, they picture iconic sculptures like the statue of Christ the Redeemer, which towers over Rio de Janeiro in Brazil; the classic paintings and sculptures in Venice, Italy; the vibrant street-art scene in Havana, Cuba … but when you think about Kingston, what stands out really? … And we have produced world-class artists,” he observes.

The protégé of towering artists like Barrington Watson, Osmond Watson, Albert Huie, Gene Pearson, Joe James, Alexander Cooper, and Nelson Cooper, who has made his living almost exclusively from his work as a multimedia professional painter for over 30 years, hopes that increasing economic development locally will fuel a renewed interest in purchasing art by institutions, professionals, the average person, and the business class.

“Young, emerging professionals, established professionals, the heads of corporations, and private and state institutions need to buy art, not just as an investment, but to develop our patrimony, our own aesthetic, our young emerging artists, our own culture so that when people think about our capital city, and indeed Jamaica as a whole, they will not only think about our great musicians and sports persons, they will not think about shanty towns and crime, but about the beauty of our murals and statues, the vibrant murals and frescoes on the walls of our new and old buildings and in our parks and along our highways,” he urges.

Art as a tool of social re-engineering

Higgins also knows the value of art in engendering peace in troubled communities. In the ’90s, he guided a mural project in Southside, Kingston, that helped to bring literacy, training, and peaceful coexistence to troubled young gang members in that inner-city area.

“I believe in using art as a tool for social re-engineering and to promote justice, especially for people in the diaspora who have been denied so much,” Higgins affirms.

He is inspired by programmes such as the Chicago Public Art Projects, funded by that American city, which includes over 500 works of art exhibited in over 150 municipal facilities around the city such as police stations, transport centres, and libraries, providing citizens with an improved public environment while enhancing city buildings and spaces with quality works of art by professional artists.

“Cities like New York have a per cent for Art program which provides that one per cent of the city budget for construction projects is allocated for public artwork. Why can’t we do something similar here among our artists to capture the energy and vibrancy of Jamaicans? I hear talk about making Kingston into the ‘pearl of the Caribbean’, that is all well and good, but there has to be an accompanying recognition that it takes some significant investments in art to make it a reality,” Higgins notes.

“We are spending billions of dollars on our roadways and new buildings. We need to make them resonate and do more than transport and house people and goods. It must tell our story, capture our glorious struggles to overcome adversity and achieve excellence. Every parish has a story to tell through art. Every parish boundary should declare its beauty, history, and diversity,” he says.