Herbie Miller | Peter Tosh – the musician and the revolutionary

“We gonna fight, fight, fight, fight, ‘gainst’ apartheid. -Peter Tosh.

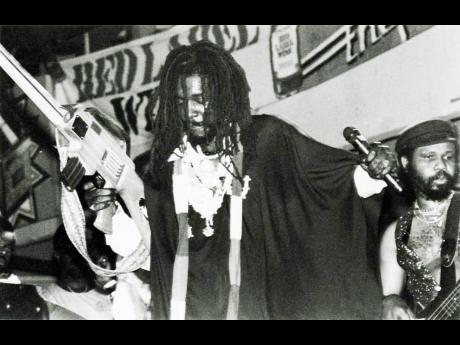

Many, to this day, consider Peter Tosh an angry, firebrand entertainer who existed in the shadow of Bob Marley, along with whom he and Bunny Wailer founded the Wailers. But Tosh was much more than an entertainer. That he was an innovative rhythm guitarist whose style has a profound influence, a performer of undeniable showmanship with commanding visibility, and a bandleader who democratically allowed the members of his group, Word, Sound, and Power, room to express themselves thoroughly is lost on his critiques.

The fact that he possessed a voice with the range, tone, and exemplary diction to be clearly understood, plus his spiritually inspired, socio-politically roused, and overall conscious lyrics means little to his detractors. Moreover, Tosh was a significant voice for Black Liberation. Therefore, he was not deterred by his critics. On the contrary, he often, in a clear but witty manner, retorted: “My music is not to make you shake your booty and get down and buggy. My music is to awaken the slumbering mentality of people, especially black people, to take them out of fantasy and illusion and bring them closer to reality” such as existed in South Africa.

“You inna me land, quite illegal, You inna me land, dig out me gold, yes;/Inna me land, diggin’ out me pearls; Inna me land, dig out me diamond/We a go fight, fight, fight, fight ‘gainst apartheid,/ We got to fight, fight, fight, Fight ‘gainst apartheid.”

SUPPORT OF EQUAL RIGHTS

Peter Tosh’s compositions, recordings, and performances are remarkably explicit and audible in support of “equal rights” and justice,” the title of his anthem taken from the 1976 recording Equal Rights. In the estimation of many, Equal Rights ranks among the best protest statements in popular culture. The recording yielded uplifting and motivational classics, including African, Get Up Stand Up, (Stand Up for Your Rights), Four Hundred Years, and Apartheid. Except for jazz drummer and composer Max Roach’s 1961 Man From South Africa, an ode to Nelson Mandela, and Tender Warriors, a dedication to the children of South Africa’s tyrannical system, Tosh’s Apartheid is the first song to address the oppressively racist Western-supported segregated system that viciously and violently oppressed blacks of which I’m aware.

“You inna me land an’ you build up your parliament/You inna me land; you build up your regime/You inna me land, only talk ‘bout justice/You inna me land, handin’ down injustice/We gonna fight, fight, fight/

Fight ‘gainst apartheid/Brothers got to fight, fight, fight

Fight ‘gainst apartheid.”

I had written in The Gleaner, on September 30, 2012, when I managed Peter, that we were approached in 1977, during the era of apartheid, by an African American representative of a South African liquor company with an offer to perform in South Africa’s Graceland for more money than he had previously earned per performance. But Peter informed the representative that he was “not interested in Graceland. He would accept the offer only if it were arranged for him to appear for Blacks in Soweto and the townships and share his earnings between the African National Congress and the sports club associated with Steve Biko.

“Africa is for Black man, remember/But the certain place in Africa Black man got no recognition/So we have to fight, fight, fight/Fight ‘gainst apartheid/Black man got to fight, fight, fight/Fight ‘gainst apartheid.”

Home in Jamaica, the Government was committed to supporting the African liberation struggles. In agreement with and recognition of former prime Minister Michael Manley’s support of South and Southwest Africa and his advocacy on behalf of so-called Third World and non-aligning nations, Peter arranged a visit to Jamaica House and presented the prime minister with a first press copy of Equal Rights with the inscription, “From one living hero to another living hero.”

“You inna me land an’ you build up your parliament/You inna me land; you build up your regime/You inna me land, only talk ‘bout justice/You inna me land, handin’ down injustice/We gonna fight, fight, fight/

Fight ‘gainst apartheid/Brothers got to fight, fight, fight

Fight ‘gainst apartheid.”

Yet and very importantly, Peter Tosh’s contribution to the global freedom struggle was not only through songs. This ardent pan-Africanist fervently acted in keeping with his musical and lyrical criticism and advocacy against injustice, particularly in Jamaica and Africa. For example, in 1967, Tosh was arrested when he singularly protested outside the British High Commission after the racist Ian Smith seized Rhodesia (presently Zimbabwe), which was overseen by the apartheid regime of South Africa on behalf of the British, with little if any consideration for the majority of its black population. Then in 1968, during the Walter Rodney “riots,” which followed the Government’s expulsion of the Black Power and Africanist scholar, Tosh hijacked a bus and ferried protesters to West Kingston when they were overwhelmed by tear gas and overpowering attacks by the police.

RECEIVED RECOGNITION

Tosh received recognition and enjoyed associations with some of the world’s progressive human rights leaders. For example, his friendship with the Black Power advocate Kwame Toure (Stokely Carmichael) resulted in performances at several anti-apartheid rallies in North America and Europe. His perspectives and sharing of ideas with the likes of Abdulla Ibrahim (Dollar Brand), the exiled South African Jazz pianist; Letta Mbulu, the singer and heir apparent to Miriam Makeba; lengthy conversations with Angela Davis, the black activist and scholar; James and Julian Bond, whose respect for Tosh’s campaign for human rights resulted in the keys to the city of Atlanta being awarded to him and the invitation and later denial to address the United Nations Anti-Apartheid Subcommittee. Peter was a bold soldier without fear.

To quote a former government minister and Wailer’s historian, Omar Davies, “Perhaps most important was the fact that his performance in raising concerns about socio-political injustices and his strong advocacy of black consciousness was not only disturbing to the status quo but simply placed him ahead of his time.” He stated that Tosh’s “strident anti-apartheid stance, long before the cause of Mandela made it a popular position to take” also contributed. In addition, the poet Jane Cortez remembered Tosh as “very supportive of and committed to Pan-African struggles. He was assertive, and revolution was within his work.”

It is for reasons such as these that the president of South Africa is bestowing on this reggae revolutionary - an artist many among us consider the embodiment of Che Guevara and Malcolm X, one who exuded the spirit of resistance to colonialism and racism and expressed unyielding love for humanity - the posthumous recognition in appreciation for his contribution to the struggle to defeat apartheid and free South Africa from its fangs.

Sadly, Peter Tosh never lived to witness the dismantling of the apartheid system. But deservingly, he posthumously joins former prime ministers P.J. Patterson and the late Michael Manley in receiving South Africa’s highest national honour for their immortal contribution to the liberation fight. “My music is to fight injustice and corruption in high and low places,” he often said. If I were not a musician, I would be an x#@!& revolutionary.

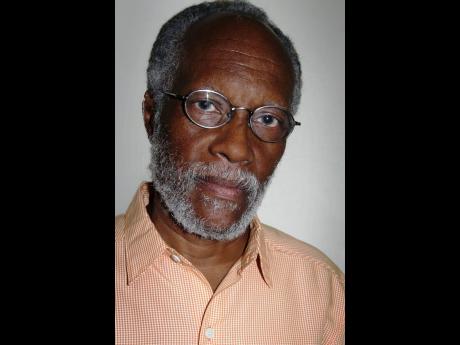

Herbie Miller was Peter Tosh’s manager between 1976 and 1982.