Ronald Thwaites | No more delay

It is a testament of how thick and arteriosclerotic the education system is, that after several years of being convinced of its vital importance, no minister, no administration has been able to really transform the quality of early-childhood education.

At the most optimistic estimate, more than a half of the teachers in this sector have little or no training. This factor alone explains the anaemic results throughout the system and has great bearing on the unsolved problems of national security and productivity.

Early-childhood specialists should be the best trained, most big-hearted and most appropriately remunerated in the profession. But the budget for early childhood is flat again this year. The talk has been good for a long time. It is action that has been wanting. The very promising Brain Builders programme, announced during Ruel Reid’s tenure, has not got off the ground. The pace of amalgamating clusters of small basic schools into well-supported infant schools has lagged. There is no excuse.

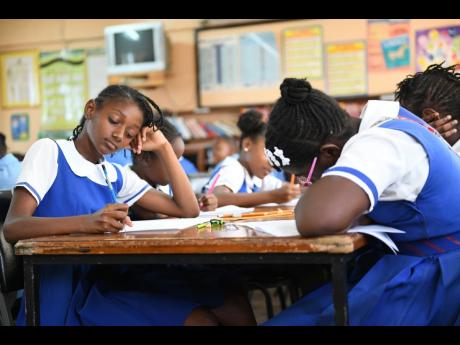

Significant numbers of our children still progress to primary school, propelled by age and not by achievement, who are neither attitudinally nor cognitively sufficiently prepared to learn. Instead, we have been investing in improving early-childhood infrastructure, which, while important, is less of a priority than stepping up the human element of those who, more often than not, have to stand in the place of inadequate parents. Improve the training, pay and accountability of early-childhood teachers now.

Once we get to the primary schools, a central issue which we are afraid of confronting is that the majority of our children are being taught and asked to read and respond in a language, the grammar of which they have not been exposed to and which, very often, they barely understand.

I acknowledge readily that for long I resisted this truth, largely because I feared that it might lead to a dilution of the critical effort to master English, the world language. A profound change of attitude, policy, curriculum and pedagogy is urgently needed to ensure the sequencing of language education from Jamaican Creole into standard English. Correcting the confusion of language over time will yield significant improvements in the outcomes of the primary sector.

When students have completed the Primary Exit Profile examination in grade six, the months between April and September should be spent intensively remediating any deficiencies of literacy, numeracy and behaviour. Once a high-school place has been assigned, a deliberate acculturation to the high-school ethos and a continuation of any required remediation must be mandatory. This will place everyone in a better position to benefit from secondary instruction. This is not happening now.

SELF-DELUSION

With regard to the high schools, let us be realistic that you can’t allocate the same per capita sum for each student if we expect some uniform threshold of outcome, which should be clearly defined as achievement sufficient to matriculate to higher learning or training – not to further repetition, as obtains now in many of the CAP and other catch-up programmes.

The truth is that many high schools are living on credit and deficit financing until the next subvention cheque comes. Recently, several of the best schools had to be bailed out. Their situation has been aggravated by the many parents, especially public servants, who have come back for the auxiliary fees they paid last September because the clear word has been given by the Government that education is free. This is a serious condition of politically inspired self-delusion. The present money just can’t stretch without parental contribution, particularly for those schools which serve poor families and which have no deep-pocketed benefactors to subsidise shortfalls.

Finally, for now, does the recent unrest at the University of Technology indicate to us that the government needs to consider moving from a model of institutional subsidy of tertiary institutions towards a system of tertiary loans and grants given to eligible and bonded students to expend at accredited institutions of their choice?

All these systemic issues, and many others, deserve full discussion and policy change urgently if we are to achieve exponentially, rather than incrementally, improved results in the shortest possible time. There should be no more delay!

Ronald Thwaites is member of parliament for Kingston Central and opposition spokesman on education and training. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com.