Basil Jarrett | Our child-bearing dilemma

FOR THE third week running, I find myself continually fascinated with the subject of Jamaica’s falling Total Fertility Rate (TFR). And it would seem that I’m not the only one as just a few days ago, news out of the United Kingdom revealed that the fertility rate in that country had hit record lows, with British women now having less than 1.5 children on average.

Official figures from the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) show that total fertility fell to 1.49 children per woman in 2022. That’s even less than Jamaica’s worrying 1.9. And as we’ve come to learn by now, both figures are well below the rate of 2.1 needed to maintain a steady population – without significant immigration that is. According to the most recent data, there were 605,479 live births in the UK in 2022, down 3.1 per cent from 2021, and the lowest number since 2002.

NEW LUXURY BRANDS

Obviously, the biggest culprit behind these numbers is the rising costs of living and child care which have prompted some women to have fewer children or forgo having them altogether. Forget Mercedes, BMW and Rolex. Children are fast becoming the new luxury status symbols in that country given the excruciatingly high cost of feeding, clothing and schooling the little rascals. But what I found particularly interesting about the UK situation is the fact that several schools in many areas, including central London, have been forced to close, due to low enrolment numbers.

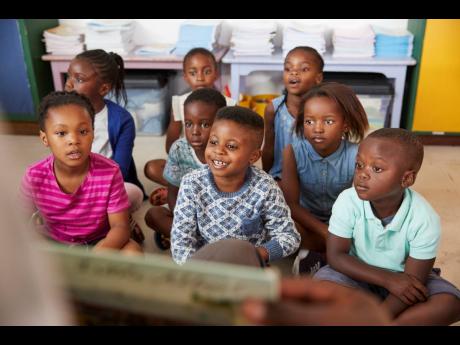

Now I do understand that while Jamaica and the UK may share a similarly low birth rate, I just can’t ever imagine schools here closing because of low enrolment and fewer children coming to school. One look at our overcrowded classrooms, bursting at the seams and I’m sure you’ll agree with me that this could never happen here.

Which prompted me to ask the question then, does a low TFR and an ageing population affect developed countries differently from developing ones?

EXAMPLES FROM AROUND THE WORLD

Well, let’s see. In the UK, today’s babies are tomorrow’s taxpayers who will pay for your healthcare and old age pensions. Fewer babies therefore mean fewer persons to provide that all-important support base. Then there is the case of Japan, whose TFR has consistently ranked below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman for decades. As a result, Japan now has a rapidly ageing population and a shrinking workforce, placing significant pressure on the country’s healthcare and social security systems and causing labour shortages and declining productivity.

Then there is China. And yes, I am aware that China classifies itself as a developing nation, but I’m not buying it. This is, after all, the world’s second-largest economy and a global powerhouse. China, however, is now beginning to feel the effects of its ‘70s era, one-child/one-family policy, which has led to a rapidly ageing population and a strange-looking demographic pyramid. China is now trying to reverse that demographic trend but the damage is already done.

THAT IVF DECISION

Then there is the US where the state of Alabama’s recent head-scratching decision to classify embryos created through in-vitro fertilisation as babies, has thrown patients and doctors into a tailspin as both could be prosecuted criminally for discarding embryos. This ruling could further compound the United States’ problem as 43 states are already struggling with their lowest TFRs in history, leading to lower school enrolment, school closures and possible hits to tax revenues later on.

As we’ve seen, ageing populations pose significant economic challenges to productivity, sustainable economic growth, productivity gains, innovation and technological advancement. In addition, the financing of pension systems and elderly care becomes increasingly questionable under these circumstances. But what is likely to happen here in Jamaica, if our TFR trends aren’t reversed?

Well, as the development experts will tell you, our declining TFR can affect various aspects of our society – not just the economy, healthcare system and pension plans as seen in developed countries. A larger ratio of elderly to younger individuals, for instance, may create shifts in family dynamics and caregiving responsibilities, thereby placing greater pressure on young people to care for ageing relatives. This may then impact their education, employment opportunities, and overall well-being, given that our history is already littered with stories of dreams being deferred due to the need to provide and care for ageing parents and grandparents.

A smaller population and ageing demographics may also hinder our capacity to develop our human capital and to innovate, to say nothing of the impact on housing and infrastructure demand.

WHAT NEEDS TO HAPPEN

So how do we move to proactively avoid these pitfalls? Well for one, don’t expect to see the ‘Anti-Two is Better Than Too Many’ campaign anytime soon. ‘Have Four, Go For More’ perhaps? In all honesty, I can’t imagine a situation where our politicians begin to encourage people to start having more children. What ought to happen is the adoption of more progressive policies aimed at promoting family planning, supporting working parents, investing in education and healthcare, and encouraging greater labour force participation among women. And for heaven’s sake, build and open more schools, not close them.

Look, I get it. Addressing the complexities of reversing our ageing population is going to require a deliberate, sophisticated and multifaceted approach encompassing both short and long-term strategies. It will also necessitate a concerted effort from government, civil society organisations, and the private sector to foster an enabling environment for sustainable population growth, socio-economic development, investments in healthcare infrastructure, greater family support, enhanced work-life balance, and of course, empowering our women.

This topic has intrigued me for over three weeks now and the deeper I delve into it, the more concerned I am that we might be asleep to the danger we’re in. It is deeply complex and delicate. All the more reason to realise that the time to act is now, as our well-being and the well-being of future generations depend on the very decisions we make today.

Major Basil Jarrett is a communications strategist and CEO of Artemis Consulting, a communications consulting firm specialising in crisis communications and reputation management. Follow him on Twitter, Instagram, Threads @IamBasilJarrett and linkedin.com/in/basiljarrett. Send feedback to colums@gleanerjm.com