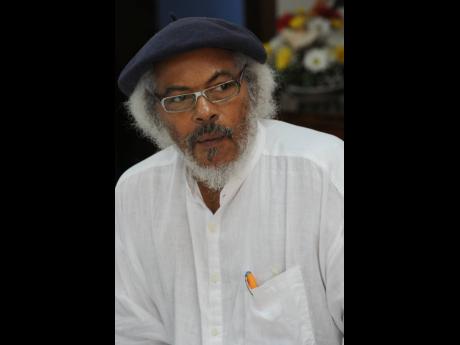

Michael Witter | Cockpit Country: Needless yu sell yu brekfus fi buy yu dinna

Last weekend, I decided to drive from the north coast through the Cockpit Country to Mandeville, in south-central Jamaica, to celebrate the life of a young friend. After several wrong turns, I picked up the road from Duncans in Trelawny to Clark’s Town, the home of the Long Pond Sugar Factory.

Frozen in a time long past, the buildings, road, and people all reflected the dilapidated state of the factory that is still grinding along in a seemingly pointless existence. The sugar industry has long been dying, but refusing to give up the ghost, and Clark’s Town has hung in there with sugar.

Another wrong turn took me on a dead straight road to Jackson Town, another relic of the sugar industry, through a vast expanse of flat grasslands that once were sugar fields. Jackson Town looks no different than Clark’s Town, conjoined, too, with the fate of Long Pond. But the straight road that the taxis now use as a racetrack reminded me of the rational layout of the sugar plantation, where roads were laid down in a rectangular grid in the first application of science to industry in history. The aim was to sequester the curves and ups and downs of the Jamaican landscape so as to maximise the efficiency of sugar production. The analogue to the sequestering of space was the regimentation of the labour force, first under slavery and, thereafter, by custom and habit.

From Jackson Town, I drove the winding road up the hill through the villages the ex-slaves built on the land they captured – the colonial government did not give them land – when they left the plantations on the plains. Here and there, amid the natural vegetation that decorated the hills and valleys, were patches of yam sticks in good order. They were not near any house, but along the way, there were houses and huts, many made of wattle and daub and some of the more modern versions enclosed with plyboard.

Here, the people, too, looked like their environment. There were old, bearded farmers trudging up and down hillsides with a machete in one hand and a bag slung over the shoulder, in clothes the colour of the earth. It was Sunday, so the women and the little children were dressed colourfully as they walked to the village church. The young ladies who were not going to church carried babies or were moving around the yards in some deliberate purpose. And the young men hung about, some smoking, most chatting, few playing, and none that I saw were working.

I was now in a space contoured by nature, with communities that were part of the environment and people who rocked with a rhythm that I imagined had more to do with the movement of the sun than the rhythm of the factory. It was a different kind of beauty from the rolling once-upon-a-time sugar fields. In fact, it was exquisite beauty with trees overgrowing the roads to form tunnels of shade, and flowers of all colours bloomed everywhere.

But it was poor, for want of material wealth, though with a sense of freedom in the absence of an imposed artificial order and in an apparent alignment with nature. It was not the poverty with depression, and a sense of entrapment – was this in my mind? – that I saw and felt in the two run-down sugar towns.

Once past Alps – I had forgotten that a village was so named – I soon arrived in Ulster Spring – first Alps, and now Ulster! The townscape began to change radically – the streets were nicely paved, with street name signs; buildings of concrete with ornate decorations were nicely painted; nuff cyar, but still, someone was riding a donkey with two hampers down main street; and some businesses posted their email addresses on their signs.

By the time I reached Albert Town – named after Queen Victoria’s consort! – I was surely in a modern micropolis. It was impressive, all the more because you could see the buildings of the past in-between some of the modern structures, and at any rate, I was a few minutes from Alps that seemed to have been frozen in time.

From there to Christiana, there appeared to be a thriving economy of new infrastructure supported by large yam fields everywhere and urban commercial services in all the towns. This was the heart of the yam belt, with no bauxite mining and only the early imaginings of ecotourism in the form of mini advertisements for tours of the Cockpit.

Here was the high point of development so far, wrought by the efforts of the ex-slaves. Before and after Emancipation, they had established villages with their food-based economy, tapped their own water supplies, trod out paths through the hills that later were paved into roads, built their own churches and schools, and passed on the knowledge of their own natural medicine from generation to generation, along with the cultural values that modern Jamaica now draws upon to project itself into the modern world. And none of this was done with the help of the IMF, the World Bank, the UN, and the other so-called international development agencies.

Still, today, the farmers and other entrepreneurs are ignored by officialdom as private investors, though they have invested everything they have. They are overlooked in favour of wooing the foreign investor, an almost messianic figure for economic growth whom technology has freed from having a permanent stake in the Jamaican economy. Come to think of it, Jamaica was the first recipient of foreign investment in human history for the establishment of sugar production on deforested lands with slave labour. With a history of foreign investment that has arguably driven our underdevelopment, why is that still seen as the source of our economic fortunes?

Recently, some citizens of the Cockpit Country and their supporters demonstrated against the proposed mining of bauxite in the area. One of the leaders of the demonstration asked why we should sabotage their way of life for, at most, 30 more years of bauxite production with marginal gains to the country, almost none of which would reach the people of the yam belt. He had posed the issue sharply, with all the historical overtones of foreign corporations continuing to displace the people from the land of their livelihood, for their private gain.

It is self-evident that the environmental and social costs of bauxite production will far exceed the monetary returns from the industry. The damage to the food economy, and the likely destruction of some of the soil and water that supports it, which have sustained the country through all economic crises, will be much greater than the short-term gains from bauxite production and exports, not to mention the threat to the basis of the culture that defines us. And I still cannot fathom why the Government does not incentivise the farmers to feed our own population, and the tourists who visit Jamaica and the wider Caribbean every year.

Forty years ago, I interviewed a farmer who was cultivating ganja and vegetables in the Great Morass (swamp) in St Elizabeth. I asked his opinion on whether the Government should allow the peat deposits in the wetland to be mined and used to fire a power station for perhaps 30 years. He looked at me quizzically and said: “Needless yu sell yu brekfus fi buy yu dinna.”

Today, instead of a big hole in the ground without vegetation, probably with stagnant water and mosquitoes, we still have the Great Morass, and his son is still planting ganja and vegetables, but now with the possibility of accessing a rapidly growing global market.

Selah.

- Michael Witter is a university lecturer. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com.