Tug-of-war over Integrity gag order

UK court ruling supports shield of privacy during probes, says Chuck

A recent landmark ruling by the United Kingdom’s Supreme Court against the publication of the identity of a person under investigation by a regulatory body could strengthen the Government’s insistence on maintaining the gag clause in the local...

A recent landmark ruling by the United Kingdom’s Supreme Court against the publication of the identity of a person under investigation by a regulatory body could strengthen the Government’s insistence on maintaining the gag clause in the local Integrity Commission Act, Justice Minister Delroy Chuck has said.

“It reaffirms my position why Section 53 (3) of the Integrity Commission Act should be retained. What the Supreme Court in the Bloomberg case emphasised is that there is a right to privacy,” Chuck told The Gleaner on Sunday.

But one of the country’s leading anti-corruption organisations, National Integrity Action (NIA), is insisting that the judgment, which many view will be very persuasive, does not support any legislative block on publication of information such as that contained in the Integrity Commission Act.

At the same time, executive director of the Jamaica Accountability Meter Portal (JAMP), Jeanette Calder, said that the ruling by the UK Supreme Court underscores that the Parliament of Jamaica has a legitimate concern regarding the potential to cause unwarranted harm to the reputation of those named as persons of interest.

However, JAMP’s position is that the pendulum has swung too far as a bid to correct one concern may have created another, arguably of equal, if not greater, harm.

In a landmark case that pitted privacy rights against freedom of expression and what’s in the public interest, Britain’s Supreme Court maintained on February 16 that a person who is the subject of a criminal investigation but has not been charged has reasonable expectation of privacy of the information relating to the probe.

The court held that Bloomberg media company violated the privacy of an American businessman when it published a 2016 article revealing that the executive was being investigated by a UK law-enforcement body.

Questions have since emerged on the implications of the UK court ruling on the raging debate here about the appropriateness of Section 53 (3) of the Integrity Commission Act, which bars the anti-corruption oversight body from commenting on any aspect of its investigations until a report is tabled before Parliament.

The so-called Christie clause is widely believed to have been in response to a practice by the Office of the Contractor General, a body now absorbed in the Integrity Commission, that used to announce its investigations.

Former Contractor General Greg Christie is now executive director of the Integrity Commission.

Chuck, who is also a member of Parliament’s Integrity Commission Oversight Committee, said the ruling supports his view that the gag should be maintained.

“Just saying that an investigation has started brings into question, ‘is something wrong?’. And even if it is shown that eventually nothing’s wrong or no misconduct emerged, a person’s reputation is still tainted,” he said, adding that Section 53 (3) “is appropriate and the Bloomberg case strongly supports that position”.

Chuck acknowledged the tension involving disclosures, privacy, and public interest, but said that “one has to be careful” to strike a balance, especially with public officials who he expects to face stronger criticisms and scrutiny.

“Even public officials like politicians still have certain privacy rights, and if a journalist engages those privacy rights without justification or truth, the journalist could well be in danger,” the minister said.

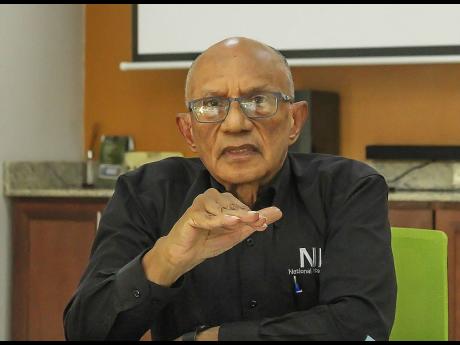

Principal director of NIA, Professor Trevor Munroe, argued that the Bloomberg decision “disrupts the balance between confidentiality and transparency which democracies seek to achieve.

“It privileges privacy and secrecy over the right of the public to information, and to an unjustifiable degree, subordinates the public interest to private considerations. This judgment risks the UK public being kept in the dark on issues which should be in the light,” Munroe said.

On Section 53 (3) of the Integrity Commission Act, the transparency campaigner argued that the ruling does not specifically justify the imposition of an “absolute, statutory prohibition on an anti-corruption body naming an individual under investigation. To that extent, it provides no justification for the retention of the ‘gag clause’.”

Munroe said unlike the UK, which has no written constitution, Jamaica’s Charter of Fundamental Rights confers “on our people ‘the right to seek, receive … disseminate information through any media’.

“This right may not be abridged, infringed nor abrogated save only ‘as may be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society’,” said Munroe.

“The ICA gag clause, without regard to justification in specific circumstances, arguably abridged this right by a blanket prohibition against us, the citizens, receiving information on whether or not an investigation into corruption has or has not commenced on an individual.”

Julian Robinson, opposition spokesman on finance and a member of the Integrity Commission Oversight Committee, said he believes the UK decision will strengthen opinions against the removal of Clause 53.

“An alternative for the Integrity Commission is to provide periodic reports to Parliament on the status of its work – quarterly or even more frequent like a month,” he said, echoing a view of the justice minister.

The Integrity Commission, last year, questioned what “mischief” would that reporting manner solve if the purpose of the gag clause was “to prevent the tarnishing of the reputations of public officials by prohibiting the IC from making a public announcement”.

The Integrity Commission, whose chairman is a former president of the Jamaican Court of Appeal, has, on multiple occasions, recommended that lawmakers amend the clause to allow it to give it the discretionary power to make “guarded comments”.

Calder, the head of JAMP, further argued that the Integrity Commission’s inability to provide any information on its investigations counteracts two “principal objects of the act”.

She pointed, in the first instance, to Section 3b of the law, which speaks to the need to strengthen measures for investigating corruption.

“Like all investigative bodies, the IC depends on public officials and citizens to share what they know. If no one knows the information is needed, it will not be supplied,” Calder said.

The anti-corruption campaigner said it also works against Section 3d of the law, which instructs the commission to “enhance public confidence that acts of corruption … will be appropriately investigated”.

Calder said the Integrity Commission should be able to indicate to the public, just like the auditor general, that an issue of public concern is being probed.

She said that there was no need to name individuals of interest but the matter that is being investigated, and when the report is tabled the details can be provided as is the current practice.

“This solves the legitimate concern of our parliamentarians without citizens being denied their basic constitutional right to information,” she said.

The Bloomberg news article was based on a letter of request that the British authority had sent to a foreign state where a company associated with the businessman was facing allegations of bribery and corruption.

The businessman sued, arguing that he was neither arrested nor charged and that Bloomberg misused his private information.

The executive, known as ZXC, won a lawsuit against Bloomberg in 2019. The media company appealed but lost, and the recent decision of the UK Supreme Court has put a lid on the matter.

“For some time, judges have voiced concerns as to the negative effect on an innocent person’s reputation of the publication that he or she is being investigated by the police or an organ of the state,” wrote Lord Hamblen and Lord Stephens in the 52-page judgment.

They argued that a growing recognition that persons should not be identified before charge “has now resulted in a uniform general practice by state investigatory bodies not to identify those under investigation prior to charge”.

They added: “The rationale for this uniform general practice is the risk of unfair damage to reputation, together with other damage.”