‘A lot of pain on both sides’

J’cans’ indifference to Windrush surprises UK journalists

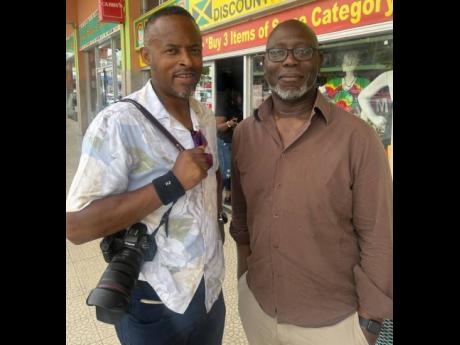

Darren Lewis, assistant editor at the United Kingdom’s Daily Mirror, and press photographer Humphrey Nemal had an enlightening discovery when they travelled to Jamaica recently on a Windrush assignment.

While the Jamaican diaspora in England had already started hosting events to commemorate Windrush Day on June 22, those at home in the Caribbean placed little significance on the day meant to celebrate the successes and resilience of their compatriots who emigrated decades ago.

“There isn’t a celebration here, with good reason. It isn’t a period that people remember with great affection here,” Lewis shared with The Sunday Gleaner.

The Empire Windrush ship left the shores of Jamaica on May 24, 1948 with approximately 500 Caribbean nationals on board. They were encouraged to move to the UK to help with post-War labour shortages and rebuild its battered economy.

After spending 30 days at sea, the ship arrived at Tilbury Docks in Essex, England, and subsequently became a symbol of a wider mass-migration movement of Caribbean people who went to the UK between 1948 and 1971.

Many of those who migrated took jobs as manual workers, drivers, cleaners, and nurses, and became known as the Windrush generation.

But their settlement in what was then viewed as the “mother country” was marred by racism, isolation and discrimination.

In 2018, following the revelation that the UK government had not properly recorded the details of people who had been granted permission to stay in the UK, which resulted in many being wrongly deported, a national holiday was declared to celebrate their contributions.

Preceding Windrush Day, educational, arts, sporting projects and activities are held across the UK to acknowledge the contributions of the Windrush generation and their descendants to British society.

These celebrations are often aimed at promoting community cohesion and understanding of the Windrush story.

Being descendants of the Windrush generation, both Lewis and Nemal not only have a vested interest in this issue through their line of work, but have lived the experience and often are also immersed in the celebrations of it.

Before boarding a flight to Jamaica a week ago, Lewis said he attended some of the events to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the voyage.

On Wednesday, a day before Windrush Day was observed in England, Lewis told The Sunday Gleaner that he was still waiting to see whether anything of similar nature would happen in Jamaica to coincide with the UK celebration.

“When I came over here, I expected to catch up with whatever celebrations that have been planned or whatever way was planned to commemorate those who left in those ships, but even at the moment, nothing has happened,” he said.

While there were no major events planned last week, Jamaica hosted a few events to mark the anniversary of the ship’s departure from the island in May. This included a church service at the Kingston Parish Church; a forum, titled Windrush 75 Reflections from Kingston Harbour’, hosted at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; and a Windrush 75 Five Communities Anchor Festival in August Town, St Andrew.

Last week, the journalists’ exploration took them as far as the parish of Trelawny, where the duo spoke with an elderly man who had made the journey to England, but subsequently returned home.

They sought to gauge Jamaicans’ connection to the Windrush story by speaking to a cross section of citizens. And while they were surprised by the indifference often displayed, they were also empathetic.

“It sounds like a lot of people do not really know about it or take an interest in the last five years, unless they came back themselves or those of the [older] generation who directly remember it,” Nemal said of his observations. He said people also felt “short-changed”, ruing that the “best had gone to the UK”, and they were left to fend for themselves.

“In England, they are celebrating and commemorating the people who succeeded against the odds. But here in Jamaica, why would you celebrate parents leaving, siblings leaving, grandparents leaving?” Lewis pondered.

Admittedly, “still processing” this reaction, Lewis, who grew up in East London with his immigrant parents from St Vincent and the Grenadines, said the Windrush story was a big part of his identity.

His colleague Nemal, whose parents migrated from Jamaica in the 1960s, tells a similar story of preservation of and pride in his Jamaican culture that was fostered by his parents and members of his extended family who also migrated.

“What we did in the house was everything Jamaican,” he said. “We live in the UK, [but] outside of going out the front door, everything was Caribbean life.”

SYSTEMIC RACISM

But lurking outside the wall of their homes where their parents worked to create a happy childhood for them was the systemic racism of British society that their parents endured and often could not protect them from.

“During those periods, the racism was so systematic that it was on TV. There were regular TV ‘jokes’ that would contain words that would be offensive to you and I, and they would use words like that to make people laugh and would do stuff that was very disrespectful towards us,” Lewis said.

He said even though the Race Relations Act of 1965 banned racial discrimination in public places and made the promotion of hatred on the grounds of “colour, race, or ethnic or national origins” an offence, a lot of people disregarded the law.

“My parents told me from the point of view that this is what we put up with, so I want you to put yourself in a position so that you don’t have to put up with it, and obviously, that meant education. The better your education, the more chance you’ve got, and you could walk away from certain situations and determine your own path, your own destiny,” Lewis shared.

This collective mindset of the Windrush generation bred their successes in politics, music, sports, television and film.

“If you think of British culture in every area, there are individuals from the Caribbean who succeeded against the odds who were able to put the discrimination to one side and persevere,” Lewis told The Sunday Gleaner.

Acknowledging however, that his perception was skewed in one direction, he noted that people who boarded that ship at the Kingston Harbour three-quarters of a century ago had the best of intentions to create a more financially stable life for their families, but their actions also contributed to the brain drain that Jamaica continues to suffer from.

“Those ships that left between 1947 and 1971, you could argue, they changed everybody’s life in Jamaica because those people weren’t here in Jamaica to help rebuild the economy after that hurricane in 1944,” he said.

The unnamed 1944 hurricane caused significant damage, including to the agricultural sector, where it destroyed 40 per cent of the coconut crop, and claimed more than 100 lives. Hurricane Charlie in 1951 would also claim more than 100 lives less than a decade later.

Nemal noted that his discoveries on this assignment were “very emotional”, as he learnt the other side of the story.

“There’s a lot of pain and suffering on both sides. There is also a lot of joy and happiness at the same time,” he told The Sunday Gleaner.