The abolition of the slave trade

The fight against slavery started with the Society of Friends, also known as the Quakers. In 1671, their founder, George Fox, strongly told the members of his society in Barbados to set the enslaved Africans free. By 1774, any Friends who were still holders of enslaved Africans would be expelled from the society, and, in 1776, it was decided that any Friend who held enslaved people should set them free.

This attitude was inspired by the Jonathan Strong (discussed in Part I) and James Somerset cases. Despite his success with Strong’s case ,Granville Sharpe, the academic who brought it to the attention of the public, was not equipped to get a legal abolition of the enslavement of Africans in the West Indies and Britain when some of them were treated as footstools, pets, and toys. While the Strong case was simmering, the James Somerset one was evolving, and Granville Sharpe was right behind it.

Charles Stewart, Somerset’s master, had brought him to England from Boston, Massachusetts. When Somerset got ill, Stewart discarded him on the streets. The Sharpe brothers of Granville and William were instrumental in getting him back to good health. Upon seeing that Somerset was fit and able again, Stewart reclaimed him, thus precipitating a landmark legal challenge in the fight for emancipation.

On June 22, 1772, Lord Mansfield, sitting on the King’s Bench, ruled that slavery was illegal in England. All enslaved people in England were to get their freedom from that day. The abolitionists had thereby achieved a significant victory. However, there was no such ruling against slavery in the Caribbean, the Atlantic Trade in Africans continued in earnest, and people were aggrandising themselves from it. Yet, antislavery agitators in Britain would not relent.

Thomas Clarkson, having researched an essay topic: ‘Is it right to make men slaves against their will?’, realised that slavery was illegal and was determined to publicise his findings. He collected first-hand information by visiting trading ships and measuring and taking samples of mouth-openers, shackles, thumbscrews, and other penal instruments. His rule was to collect and publicise information in order to elicit public opinion so that there would be an outburst of public protests to Parliament which would help to bring about the abolition of slavery.

CHAMPION IN PARLIAMENT

But it seemed like only an act of Parliament could bring an end to chattel slavery. Thus, the abolitionists realised that they needed a spokesman in Parliament, a champion of the fight against slavery. William Wilberforce was the man. It was William Pitt, the young prime minister of England, who influenced Wilberforce to enter Parliament, who regarded it as a place where he could best serve God. He had been converted after coming under the influence of the religious revival in England led by John and Charles Wesley.

In the House of Commons, Wilberforce was assisted by Fox and Pitt. His speeches were eloquent and convincing. Long hours were spent trying to win the support of his fellow members of Parliament for abolition. His campaign met with many setbacks and disappointments, in and out of Parliament, but Wilberforce persevered.

The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded in 1787. Its main role was to win the support of the public through the publication of pamphlets and newspapers, and through Sunday sermons. These would result in petitions being sent to Parliament. The abolitionists worked hard and were gradually reaping success. There were counter-campaigns by the West India Interest – stakeholders were benefitting from slavery – but these were met with little success.

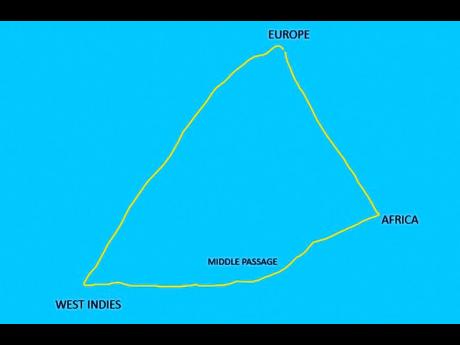

The policy of the gradual abolition of slavery was adopted by the British Parliament. Slavery would be gradually abolished over a period of time. The Abolition Bill was passed in 1807, to be effective on January 1, 1808. It was a legal end to the Atlantic Trade in Africans, but not to the institution of slavery itself in the West Indies. Fines and penalties were to be imposed on all British traders in Africans who would not comply.