Conservationists make Headstart at keeping Jamaican Iguana safe

It was a remarkable discovery when the Jamaican Iguana (Cyclura collei) reappeared in 1990 after being thought to have gone extinct for nearly half a century.

They were once commonly found along the south-central sections of Jamaica and on the Great Goat Island, but now a fairly large population of the species can only be found in Hellshire Hills – a region of dry limestone in St Catherine which forms part of the Portland Bight Protected Area.

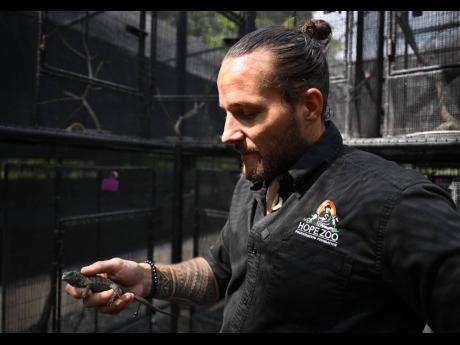

Improving their survival rate is the ongoing goal of the Headstart Project which is run by the Hope Zoo Preservation Foundation (HZPF). Although it was launched in 1991 with grant funding from the Global Environment Facility Small Grants Programme (GEF) and carried out by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the species remains a critically endangered one.

Joseph ‘Joey’ Brown, conservation biologist and curator at the HZPF, explained the programme’s methodology in an interview with The Gleaner last Wednesday. It comprises the collection of hatchlings from the wild which are taken to the Hope Zoo to be raised until they are about four to six years old and mature enough to escape predators after being reintroduced into the wild – providing them with a “head start on life”.

‘Saving grace for the species’

To date, more than 700 iguanas have been released into the wild since the project’s first release exercise in 1996.

The goal is for 1,000 iguanas to be released by 2026, “which will be the saving grace for the species,” Brown said.

“A thousand (iguanas) sounds like a small number, but it’s a big number in the aspect of what is being done for the reintroduction into the wild,” he said, adding that there were only a few adult female iguanas among the approximately 20 adult iguana population rediscovered in the 1990s.

Previously, the zoo’s Headstart facility could only house some 300 iguanas. Now, with a total expansion conducted in 2017, the facility can hold more than 500 iguanas.

Every hatching season, Brown said, only 40 hatchlings were taken back to the zoo from the wild. Now, around 150 hatchlings can be brought in, increasing the potential release size to about 80 to 100 iguanas annually.

The long-term goal of the project is the reintroduction of iguanas on to Great Goat Island after raising funds to eradicate all the invasive species from it. After this, it is expected that the species will be able to flourish on their own.

The Jamaican Iguana, Brown said, were incredibly important for the ecosystem as they provide great benefits to the forests which in turn benefits all native wildlife.

Continuing, he stated that because they consume native fruits and plants and aid in spreading those plant species by breaking down and excreting seeds back into the forest, they were said to be “Jamaica’s first farmers”.

He further explained that research indicates that seeds that have made it through an iguana’s digestive tract germinate more quickly as the harder layers of the seeds are broken down prior to excretion.

As such, they are also characterised as “ecological engineers”, he said.

The primary threats to iguanas are invasive predators, including wild dogs, that consume both large and small iguanas; wild cats, that consume small iguanas; wild pigs, that eat the eggs and destroy nests; and non-native mongoose that eat small iguanas and their eggs.

Goats also compete with iguanas for food and typically destroy the iguana habitats.

Although hunting, killing, and eating iguana was once common among humans, it is not thought that this was a major contributing factor of the species’ extinction. It is also no longer practised.

This is an illegal activity, however, as the reptile is protected by law and individuals who capture or kill iguanas may be subjected to one year in prison or to pay a fine of $100,000.

Other threats to the specie and its habitat which are caused by human activity include the illegal cutting of trees for charcoal production in the Hellshire Hills; infrastructural development such as for tourism or housing in the areas where iguanas live and quarrying.

Additionally, climate-change threatens their survival. The environments which they currently inhabit have the potential to become too hot due to rising daily temperatures. Drought can lead to a reduction in food supply resulting in starvation.

Health screened

There are four rangers who conduct daily monitoring of the iguana habitat; they also help to eradicate invasive species by setting 200 to 300 traps.

Each year, the iguanas are health screened by scientists and veterinarians. During this time, their body measurements and weight are taken; blood and faecal samples are collected, and observations made to check for injuries or abnormalities.

Brown noted that, thankfully, there has been no detection of diseases affecting the species.

He proudly indicated that, in 2008 the first documentation that the iguanas which were released into the wild had started to reproduce, a positive indication that the population will increase.

Before they are released, an electronic Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT) tag reader containing their medical history is inserted beneath the skin. This contains a quick-response code with a unique identification number that allows for lifelong tracking of each iguana.

What can Jamaicans do to help as experts continue their efforts? Well, according to Brown, the most important step is to become knowledgeable about the importance of the Jamaican Iguana to the environment.

“We’re not asking people to love iguanas, we all know that Jamaicans often have a fear of reptiles, especially lizards ... but, respect them like reggae music or any part of our history and is part of the Jamaican culture,” he said.

Collectively known as the Jamaican Iguana Recovery Group, other local and international stakeholders involved in the Headstart project and the implementation and management of the Jamaica Recovery Plan (2013) include the National Environment and Planning Agency; the Urban Development Corporation; The University of the West Indies; Caribbean Coastal Area Management Foundation; the Institute of Jamaica; the International Iguana Foundation, the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Species Survival Commission iguana specialist group; Forth Worth Zoo and San Diego Zoo under the umbrella name of the Jamaican Iguana Recovery Group.

Fun Facts about the Jamaican Iguana ( Cyclura collei ):

They are the rarest of all the 44 species of iguanas globally.

They are among 28 reptiles endemic to Jamaica.

Jamaican Iguanas can grow up to 1.5 metres long and weigh up to 6 kilograms (13 pounds).

The nesting season for the female Jamaican Iguana is May.

Female Jamaican Iguanas can lay to 30 soft white eggs in the deep burrows they dig in red dirt. After three months, the eggs will hatch, and the hatchlings will have to scratch their way to the surface.

A Jamaican Iguana’s diet includes fruits, leaves, seeds, and flowers as they are mainly herbivores.

The Jamaican Iguana has three eyes. It’s third eye is called the pineal eye and is a light-coloured scale on the top of the head which is sensitive to light and the dark.