Religion & Culture | Mixed emotions at slave museum

It is sticky hot and it’s merely 9 a.m. I am at the entrance to the slave museum, also called the Ouidah Museum of History, once home of the Portuguese slave fort.

It appears small in comparison to the palaces of Abomey and Porto Novo that I visited in January. Ouidah is special to me because it is the de facto spiritual capital of Benin.

A slender young man greets me. He introduces himself as Oscar Koba. Seconds later, he apologises for his less-than-perfect English, but in a country where English is as infrequently heard as crickets in New York City, I am already impressed.

It does not take long for him to grab my attention.

“This is the only remaining European fort,” he says. The rest having been erased by the Danes, the British, the French and the Dutch, a fruitless attempt to hide their involvement in the plunder of this country. But scars are never easily removed. After the slave trade ended, the Portuguese remained and used the fort as a diplomatic and administrative centre, a country within a country, according to Koba. That unofficial status was in force until 1961 when they were forced out when Dahomey (now Benin) won its independence. I ponder on its significance of the year. “That’s the year I was born,” I blurt out, as if there was some mysterious connection between the two occasions.

Immediately after Dahomey claimed independence, the Portuguese, sore ‘tenants’ they were, burned the fort while escaping by sea with its valuables.

I can’t help but show my displeasure at the non-response by the new government, only to be reminded by Koba that a nascent Dahomey was in no position to start a war with another European country. The Dahomey-French wars had visited enough horrors on this country.

We move from room to room observing artefacts and relics: cowrie shells used as currency, smoking pipes, vases and a fancy bottles of whisky once savoured by Ouidah’s kings. “One of these pipes was exchanged for two or three slaves, depending on their physical condition,” Koba breaks the silence.

What a waste, I say to myself, and curse the kings in my mind.

Decapitated heads

This was astounding, but not more so than a framed picture of the flag of Dahomey. I can’t believe my eyes: A flag that bore the drawings of bound slaves, machetes and decapitated heads. This was Dahomey: unapologetically autocratic, bloodthirsty and openly complicit in the slave trade. I experience an apoplexy of anger and sadness.

I ask Koba for permission to photograph the flag, well aware that filming, recording and photography are prohibited inside the museum. I implore him, trying desperately to win his favour, but to no avail. I correct myself, embarrassed.

And for a minute, I am done defending Africa’s kings.

I compose myself and put the blame squarely on the self-serving avarice of the kings, and the kings alone. The slave trade decimated the African collective. I need to remind myself of the truth.

I begin to appreciate Koba more as the tour proceeds. I find him to be astute and resourceful. He makes mention of the tactfulness of the first Portuguese that arrived on the shores of Dahomey. It is a lesson that we (black people) should learn, and learn fast. “The Portuguese came with a plan.” Koba calls it the 3Ms. He illustrates with his fingers.

“The missionaries, the merchants and the military,” he says, emphasising the order of their well-executed plan.

And out of sheer greed and short-sightedness, the kings of the competing kingdoms fell for it, one by one, cut down by their own naivety and an enemy that exploited it.

I am exhausted by my thoughts; so many unanswerable questions. What if the kings had rejected Europe’s overtures? What if they had buried their differences and fought to protect the integrity of the land? What if? What is?

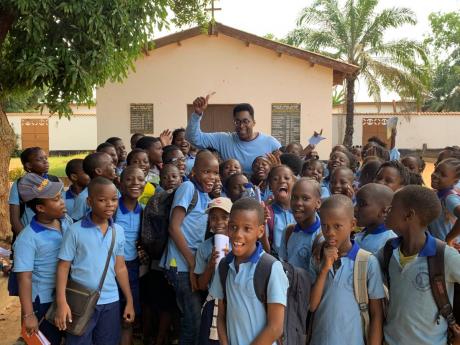

Koba and I part ways amid the jubilant sound of schoolchildren in the courtyard. So spirited. Not a care in the world except for passing exams and finding favour with parents, teachers and peers.

They are not assembled, so I move close to get their attention. We lock eyes, like magnets. They are smiling. I am smiling. Curious harmony. My disappointment in humanity now falls off like a snake shedding its skin, only faster.

Two sayings from the scriptures come to mind: “Suffer the children into me” and “A little child shall lead them.”

I am taking pictures of innocence. I am now in the pictures, a passer-by shooting away. I am being healed from the anger and frustration over the slave trade.

But nothing is forever. The children are called to assemble.

Goodbye, goodbye, they say in French. Some have to be peeled away from me. I don’t want this experience to end either. That is love. This is truth.

And a saying comes to mind: Brutality is short-lived but love endures. And I repeat it, again and again.

Brutality is short-lived but love endures.

- Dr Glenville Ashby is the author of the award-winning audiobook Anam Cara: Your Soul Friend and Bridge to Enlightenment and Creativity. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com and glenvilleashby@gmail.com, or tweet @glenvilleashby.