Stanberry bares all in treatise on liberalisation of sugar industry

The treatise by Dr Donovan Stanberry, registrar of The University of the West Indies (UWI), Mona campus, How Trade Liberalization Affects a Sugar-Dependent Community in Jamaica: Global Action; Local Impact is a damning indictment on the failure of successive political administrations, ministers of agriculture, managers of the sugar estates across Jamaica and other stakeholders who held key portfolio in the local and regional industry, some of whom still hold these positions, and their role in condemning entire communities in sugar-dependent areas (SDAs) to a state of penury, from which they have been unable to extricate themselves.

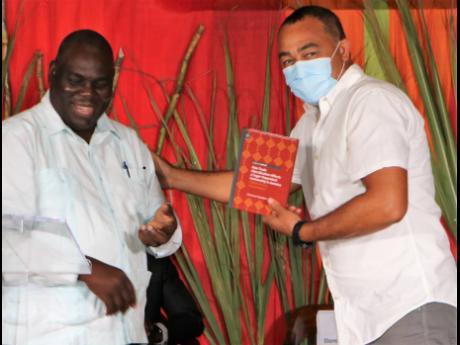

At last Wednesday’s launch at the Undercroft of the Mona campus, which included readings from the book that is now available from Amazon and which will be in the UWI bookstore two weeks from the launch date, Stanberry, the former permanent secretary in the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, brought to light some disturbing revelations, clarified some myths, and offered insights into experiments which went woefully wrong and left the residents of his beloved home town of Vere, Clarendon, and other SDAs mired in poverty and locked in a vicious, unending cycle of lawlessness.

This, despite an investment of some 84 million euros by the European Union (EU) under the Banana Accompanying Measures, which were a programme aimed at the diversification of the economies of the SDAs and which former Agriculture Minister Roger Clarke characterised as a funeral grant.

The programme for social transformation of SDAs commenced in earnest in early 2009 following the development of the Sugar Area Development programmes in 2008, through which the Government expended over $9.3 billion in all the SDAs in Jamaica, including over $2.2 billion in the Vere area in Monymusk, Clarendon. This money was distributed in the form of grants to vulnerable workers who were made redundant, and also spent on housing development, cane road expansion, development of agro parks, skills training, rehabilitation of sporting facilities, and a variety of small infrastructure projects.

According to Stanberry, this programme represented the most expansive in scope and intensity in terms of socio-economic programmes ever implemented.

Ironically, and tragically, despite this big spend by successive administrations, the net social impact of the failed divestments has been manifested in the SDAs in the reduced numbers of entertainment events in the communities, reduced support for sports, and a marked rise in criminal activities, notably praedial larceny, according to Stanberry.

He charged that the empirical evidence from the research reported in the book, gleaned from interviews and surveys of former sugar workers and residents of the Monymusk area, as well as the case study of the wider Monymusk area, indicate that residents did not perceive any improvement in their lives.

“Residents stated that their quality of life worsened, although they were (only) able to meet their basic needs, thanks to remittances and the help of family. Vere is the only place in Jamaica I know that looks worse today than 40 years ago, and this is not being hyperbolic. Nothing has been able to replace the sugar cane to date,” he told the audience. Sugar production has declined every year since 1965, when production peaked at over 500,000 tonnes

In fact, Stanberry blames inertia and a seeming intellectual paralysis on the part of all the aforementioned stakeholders as the single greatest reason for Jamaica’s failure to modernise its sugar cane industry and shift to the development of other by-products of sugar, such as bagasse for generation of energy, ethanol, and even plantation white sugar, as Belize and Mauritius did in the face of collapsing preferential markets.

The writing was on the wall in bold and bright lettering from as early as the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade negotiations from as far back as 1986, when there was a global stirring to free up agricultural trade.

“So, successive governments have to shoulder some responsibility for this lack of modernisation, not only as the major producer of sugar since the late 1970s, but especially for resisting the attempts of private estates to transition to mechanised harvesting. These attempts were resisted because mechanisation, while it would increase efficiency and profitability in the sector, would eliminate the need to employ large pools of semi-skilled people in the sugar belt.

“This inertia with respect to investment in the sugar industry is puzzling, given the critical importance of the sugar industry to the nation in terms of foreign exchange earnings, employment, and maintaining the social fabric of the SDAs. Could this paralysis on the part of government and other industry players be symptomatic of a deep-seated dependency that the plantation economy engendered over such a long time? Could this inaction serve to perpetuate poverty in the SDAs, with the industry only as a large sponge to mop up the large pool of rural unemployed people and to keep them on low-paying jobs?” the former permanent secretary posited at the launch.

“No ACP (African, Caribbean and Pacific) country, no government with any ministry of foreign affairs that is worth its salt could deny that the move to liberalisation of agriculture trade was long in the making and was intensified by the year, but we were paralysed and we did little.”

Government’s involvement and investment in the sugar industry started in 1970 under the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) administration of Hugh Shearer, when the United Kingdom-based company Tate and Lyle, which had a 70 per cent stake in the industry, signalled its intention to get out of sugar cane growing, but held onto the factories in order to maintain the rum distillation aspect, which was the lucrative part of the industry.

So in 1970, the Government bought Monymusk Sugar Estate in Clarendon and Frome Estate in Westmoreland from Tate and Lyle, and Bernard Lodge in St Catherine. But it was in 1972 that the State really got involved, and the Michael Manley-led administration of the People’s National Party (PNP) started the sugar co-operative experiment. This was at a time when all the sugar factories started collapsing under the weight of increasing debts and a lack of profitability that government became the main player and formed the National Sugar Company.

Following the failure of the sugar co-operative system, which he described as a noble experiment with good intentions, in 1993 the PNP, under Manley’s leadership, initiated the first round of divestments. Stanberry, who worked across both JLP and PNP administrations as permanent secretary, was scathing in his assessment of what transpired.

“It was literally handing the assets, including the factories, to private individuals, and that also failed. Within four years, the estates were handed back to the Government for $1, but with a $2.8-billion debt. The two interventions by the Government, up to the last one, which is more the subject of this book, were in fact failures,” he declared.

By 2010, the JLP had formed the Government and Minister of Health and Wellness Dr Christopher Tufton was in charge of the agriculture portfolio at the time. He attended the launch, and offered an explanation that the divestment process was in fact an exercise in futility. He disclosed that the Chinese were not the investors of choice.

“The truth is that the industry had got to a stage where unless it was heavily subsidised, it really just could not function. When we attempted to dispose of the assets, when it was exposed to a potentially willing buyer, there were not many takers. The Chinese, I think, represented the fourth stop. I think we started with Infinity Bioenergy out of Brazil, then we travelled to Italy, we approached, I think, a US entity. I understand that they flew over in a helicopter and didn’t bother to land, having just looked at the state of the estates, and eventually we ended by having the Chinese and, of course, a local group that came in, and we almost could pay them to take the assets that were left here.”

Should Stanberry shoulder some of the blame for the colossal failure to properly divest the sugar industry, as well as the state of the SDAs in the wake of the accompanying measures, given his pivotal role as permanent secretary during this critical period?

Responding to Tufton, whom he admitted was a hard task master, Stanberry offered this rationale for what transpired then.

“In hindsight, minister, I think that there is no way that the Government could carry … well, not in hindsight. I knew, even from then, there is no way that the Government could continue to carry on the national Budget nearly $40 billion worth of debt, and that is in the post-FINSAC period. We worked hard and we achieved that, and the book gives the Government every commendation in terms of the social programmes that we undertook, spending over $9 billion in sugar-dependent communities over a short time. It’s not a small thing.

“I even became a contractor. I had to go to Westmoreland, every week on the road, making sure that the houses were built; having NEPA (National Environment and Planning Agency) suing me and the Ministry of Health suing me because the proper sewage system was not in place. So it was hard work that was necessary, but not sufficient.”