W. Adolphe Roberts: 'Father of the Nation'

Ken Jones, Contributor

Next year when we are celebrating the 50th anniversary of political Independence, some thought, I hope, will be given as to who should wear the heroic garland for conceptualising and initiating the march towards Jamaican self-government. It wasn't Norman Manley, who was drafted into the movement in 1938. It wasn't Bustamante, who bided his time and seized the crucial moment in 1961. It was the dual citizen Walter Adolphe Roberts who began and vigorously promoted the campaign, beginning September 1, 1936.

Roberts was born in Kingston in 1886, and at the age of 16 was a Gleaner reporter, associating with great journalists such as Tom Redcam, who subsequently was recognised as the first Poet Laureate of Jamaica; and Herbert George deLisser, generally regarded at the time as one of the finest editors in the West Indies. He migrated to the United States in 1904 and there developed into a leading historian, poet, and journalist. He was war correspondent for a New York newspaper and authored several books, including his best-known historical work, The Caribbean: the Story of Our Sea of Destiny.

In 1936, Roberts launched the Jamaica Progressive League in New York. The organisation's primary purpose was founded in the belief "... that any people that has seen its generations come and go on the same soil for centuries is, in fact, a nation". The pledge of the founders was "to work for the attainment of self-government for Jamaica, so that the country may take its rightful place as a member of the British Commonwealth of Nations". The first branch of the League was organised and led by W.G. McFarlane in 1937; and he invited Roberts and the others to come to Jamaica to help energise the campaign; and they did so in December 1937.

Thereafter, Roberts devoted much of his time and money campaigning for the cause in American cities where Jamaicans lived; travelling with the message throughout Jamaica and working with Jamaican organisations, including the National Reform Association, the Federation of Citizens' Association and the People's National Party, which, when it was founded in 1938, adopted his proposal. At first there was division in the PNP on the matter. Some party members opposed Roberts' position, preferring representative government with a constitution such as Jamaica had prior to becoming a Crown colony in 1866.

Bustamante and Norman Manley deserve their places in the history of our Independence; but we should also raise a memorial to Adolphe Roberts whose focus was unwaveringly on self-government for Jamaica. There were times when others argued, with some justification, that the country and its people were not ready for political independence. There were suggestions that Jamaica could not go it alone. Roberts never relented, although he acknowledged that the road to self-determination would be long, but exciting.

Not fit for government

In 1938, after the formation of the PNP, even Norman Manley was cautious. In a published statement, he declared:

"I have said before, and I will say it again, that aiming at self-government, the People's National Party does not pretend to say that we are, at this very minute, right up for self-government. We are not right for it because we have not learnt unity and discipline and organisation. We are not fit for such a government until we can sweep away the stupid class prejudice, and until we can unite in a common platform, and until we can get more honest politics and more honest politicians, and until we can put away graft and men cannot be bought in the Legislative Council.

"If we cannot secure that unity and loyalty, it is just as well that we do not bother with political life at all. It is not bringing us one step further on the road to manhood: in the road on which we will be able to govern and control and look after our own affairs in this country."

Following a lively debate and vote at the party conference on April 12, 1939, the PNP formally adopted the proposal for "complete self-government and universal adult suffrage".

Bustamante, who had always supported the idea, also expressed caution up to 1950 when he told the House of Representatives:

"We believe that whilst we should and must have full ministerial rights, we do not feel that this is an appropriate time to ask for what I call complete self-government ... . Not because we on this side are not working for full self-government ... but because we think we can fly too far and not find anywhere to perch.

"I know full self-government appeals very strongly to individuals who do not understand ... . We do not believe it will be in the interest of this country now. We will be ready a few years from this when there are less wild politicians."

The influential Gleaner newspaper also wanted to wait and see. In a 1941editorial, it advised:

"Various groups in Jamaica appear to be signifying their approval of the advocacy of immediate self-government; other groups prefer some other system, with an interval of time for more social and political education and improvement before self-government is considered. As a matter of fact, we do not believe that 50 persons in Jamaica anticipate complete self-government within the next 20 years, or even really desire it ... .

"We are thinking, of course, of those in Jamaica who are the people that, in a matter like this, must really count. They did not originally advocate immediate dominion status or the immediate granting to Jamaica of responsible government; they do not talk about dominion status even now ... . It was in New York that a number of natives of this island (most or all of whom have become American citizens) who founded an organisation called the Jamaica Progressive League."

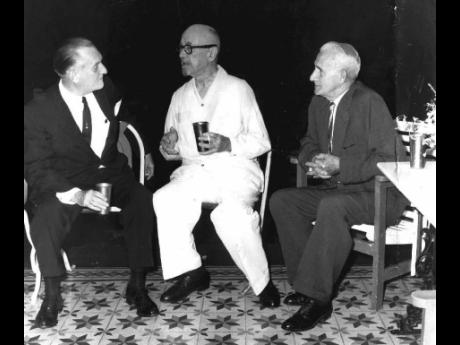

For all that, Adolphe Roberts and his supporters knew that the work had to go on and that they could not merely watch and wait. Nor would they be diverted by any regional interests. At a birthday celebration for him in Jamaica, he explained:

Didn't like the idea of federation

"When we founded the Jamaica Progressive League in New York in 1936, the object was to obtain self-government for the island at the earliest possible moment. By that we meant independence as a dominion or under any other name that Britain would concede.

"We did not mean home rule or any new concept nation such as a Caribbean federation. We studied the possibilities very carefully and concluded that we should be lucky if we attained our ends in 20 years. I realised that the logical course was to progress from the simple and fundamental to some more elaborate programme later on."

He did not like the idea of federation. Of that political arrangement, he said:

"Federation is like marriage. You really ought to have at least the illusion that you picked out the girl, even though your daddy may have chosen her for you! It is a solemn contract. But marriage has to prove a success, or it is likely to end in divorce."

Roberts was prophetic. The West Indies Federation ended in divorce and vindicated his belief that Jamaica should be independent on its own. In pressing for due recognition of this great son of Jamaica, I should mention that apart from giving of his outstanding scholarship and political sagacity, he served Jamaica in many other ways. He was head of the Jamaica Historical Society (1955-57), Jamaica Library Association (1958), The Poetry League of Jamaica and the Natural History Society of Jamaica. He was also chairman of the Board of Governors to the Institute of Jamaica at the time of his death.

Walter Adolphe Roberts fought a great battle for Jamaican self-government within the British family; and on the eve of Independence, in 1961, the Queen of England awarded him the prestigious order of Member of the British Empire. Ironically, when Independence was declared in August 1962, the new Jamaican Constitution banned him and the other pioneers from any participation in Jamaica's parliamentary affairs. Six weeks later, at the age of 76, he was dead.

It was 15 years after his death that Jamaica remembered to honour Adolphe Roberts with the posthumous award of the Order of Distinction (Commander), the equivalent of what he had received from the British Queen in his lifetime.

Next year will be time enough to correct this error of omission and to give honour where it is due to the true pioneers of self- government for Jamaica; men such as Roberts, Ethelred Brown and Wilfred Domingo, the man who introduced the ackee to the United States and who, on returning to Jamaica, was put in detention for 20 months without charge. Having chosen not to become an American citizen, he was, after his release, banned from re-entering that country until 1947. The names of these pioneers should be inscribed on some prominent monument mounted in National Heroes Park. They deserve no less.

Ken Jones is a veteran journalist and communication specialist. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com and kensjones2002@yahoo.com.