Frightening!

Educators shaken by minors’ graphic stories of parents’ crimes, fear for their development without early intervention

It’s abnormal. It is untenable. And except for drastic interventions as early as the kindergarten level, there seems no end is near for Jamaica’s runaway crime problem, some educators believe. There are also long-standing calls for the severance of...

It’s abnormal. It is untenable. And except for drastic interventions as early as the kindergarten level, there seems no end is near for Jamaica’s runaway crime problem, some educators believe.

There are also long-standing calls for the severance of ties between politicians and organised criminals to put an end to the bloodletting. But to the ordinary folks facing the harsh realities daily, those are “bigwig” aspirations, the foremost plea of members of the private sector, The Sunday Gleaner has found.

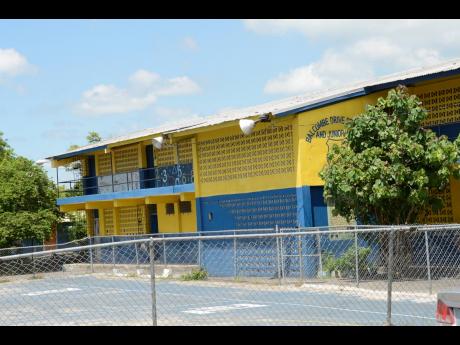

Here, in the twisting lanes of one of Jamaica’s grittiest enclaves, curbing crime is much more intimate, and staff at the Balcombe Drive Primary and Junior High School are reminded of that each day - facing acceptance, apathy and nonchalance from both their young students and parents.

Two days after welcoming parents and students back from the summer holidays, the St Andrew-based school was forced to close its doors last Wednesday, a day after gunshots rang out metres away, killing two people on the spot and leaving a third injured.

Killers on motorcycle

The killers were on a motorcycle, and as police combed that crime scene, gunshots echoed on nearby McDonald Place, where three more persons were shot, two of whom also died. The incidents follow a double murder days before and police sleuths believe they are all linked.

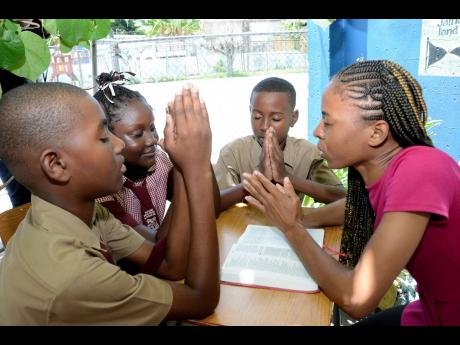

Balcombe Drive Primary and Junior High also houses an infant school, and teachers say the impressionable minors speak openly about their experiences, some of which involve their parents’ heinous criminal acts.

They usually do not understand the consequences, and sometimes share graphic details that make the adults’ blood run cold, leaving them with internal fear and fright.

“There are students here, as young as infant school, who based on their behaviour and some of the things they tell you, we know there is going to be trouble without serious early intervention,” stressed one educator.

She listens to the children and offers comfort. Sometimes, however, what she hears is most chilling, even for an adult.

“We have students whose parents are involved in violence. They will tell you how they see their relatives hiding out on the roof,” she relayed, carefully selecting aspects of her insights as she spoke. “Sometimes the kids just talk. Sometimes they don’t even know what they are saying.”

Some stories leave the educators fearful for their lives. They make them hesitant at times to visit some homes to attend to the children in need. Anything can happen, they say, from gang retaliations to police raids, and they dread being caught in the middle of either.

“It affects the students mentally and emotionally. It affects them socially. And when it affects them, it affects us as well,” one teacher lamented. “Now we have to find new strategies to reach these children, and sometimes I feel incompetent. Sometimes I go home in tears.”

The tears are particularly for the boys, a majority of whom are direct witnesses to some of the most horrific crimes in their communities.

INDIFFERENT TO VIOLENCE

For many of the children, their social skills are poor. They are unnaturally disrespectful to teachers and hold warped theories about the role of police in the areas they live.

“We had a policeman here and he was asked by one of our young boys what the stripes on his shirt meant. The cop told him it represented his rank,” said another educator. “What shocked us is when the student said, ‘Oh, because I thought it showed how many people you killed’.”

Three decades at the school and Principal Yvette Foster has seen the institution close its doors dozens of times as a result of gun violence. It is for the students’ and staff’s physical and mental safety, but some parents have grown so indifferent to the violence that they complain.

“It was so surprising that parents were quarrelling that we decided not to keep school after the incident,” Foster shared with The Sunday Gleaner last week, recounting the influx of security forces in the area afterwards. “They didn’t see anything wrong with it.”

Nonetheless, she explained that the flare-up in violence will impact early registration even as the school plans a special welcome for students tomorrow.

Up to last Wednesday, 1,055 murders had been recorded in Jamaica since the start of the year; a seven per cent increase compared to last year. Shooting incidents are also high at 813. The St Andrew South Police Division, within which Balcombe Drive falls, reached the 100-murder milestone last week.

“This is their way of life. Death and violence have become the norm for a lot of the residents of these communities, and it is going to be hard work to get them to see differently,” charged Superintendent Kirk Ricketts, who heads the division, which is riddled with squatter settlements.

“It is going to take a significant culture shift. It will take having them live for a time without these kinds of violence for them to realise what life could be without weekly or monthly loss of life,” Ricketts theorised.

One person of interest has been taken into custody in relation to last week’s shootings. Several others are on the lam, and Ricketts is hoping frustrated residents will give them up. That is easier said in these parts, however.