‘Pregnant While Black’ in America

Jamaican ob-gyn tackles challenges childbearing Black women face in the US in new book

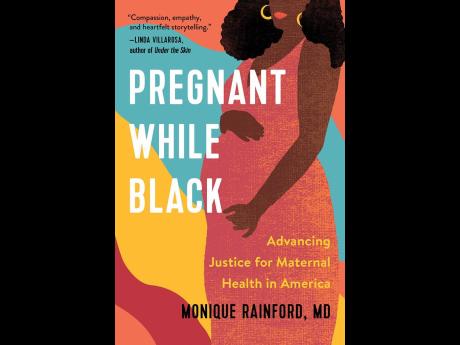

Jamaican-born obstetrician gynaecologist Dr Monique Rainford has been causing quite a stir in the United States with the release of her new book, 'Pregnant While Black'.

The book seeks to address the issue of maternal health and justice in America and was inspired by Dr Rainford's observation that the infant mortality rate for Jamaican babies was better than that of black American babies. Even more troubling was the fact that the mortality rate for black American babies doubled that of white American babies.

“I was troubled by the fact that poverty was often cited as the main reason for the high mortality among black American babies,” said Dr Rainford, who was trained at some of the most prestigious medical institutions in the world, including the University of Pennsylvania, Harvard Medical School, and Georgetown.

Her book aims to challenge this assumption and spark a conversation about what can be done to improve maternal health outcomes for all women in America.

“I discovered this was not about poverty, but about racism proven by the health disparities that exist for black women in America. I grew up in Jamaica, there is poverty in Jamaica. You can't say to me Jamaica is less poor than America overall. That obviously doesn't make sense.”

Not only are babies dying, owing to the disparities, racism and implicit biases, but being black and pregnant is like signing a death sentence for thousands of women, and these numbers rose steeply during the COVID-19 pandemic, she said.

“For black pregnant women in 2021 per CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), the death rate was 69.9 per cent per 100,000. For white women, the number was roughly about 26 per 100,000. Pre-pandemic in about 2019, it was about 44 per 100,000 for black women,” were the alarming figures that rolled off Dr Rainford's tongue during an interview with The Sunday Gleaner last week.

“So it has increased each and every year since 2019. We don't know what 2022 statistics are yet because it takes a little time, but we know it got worse in the pandemic. And, of course, that's not surprising, because frankly it got worse for all women, but that great disparity remains.”

'IMPLICIT BIAS'

The former Immaculate Conception High School graduate, who grew up in Kingston, said it was frightening to see that the disparities are worst if a woman is of the highest socio-economic status, explaining that “for a higher socio-economic status black woman, compared to a higher socio-economic status white woman, the difference between outcomes is worse in those two groups”.

She said racism is evident in many ways, including the kind of care offered to a black woman and a white woman at the same institution.

“And why does that happen? One of the reasons it happens is because of something called implicit bias,” she stated.

Implicit bias is an unconscious bias, which is evidenced in the treatment received from people who are taught certain myths about blacks over the years.

“A person who means well may believe these myths about black people, like they don't have the same sensitivity to the pain, or their concerns shouldn't be taken as seriously,” Rainford explained.

“And so they start giving less good quality care to black women, and that less good quality care can lead to morbidity, which is like a bad outcome, or increased death.”

She acknowledged that black people are part of the problem, but they balance out the impact.

She also admits that she didn't expect to see this type of disparity in a first world country and that is why she was so startled when she discovered the data in medical school. “It didn't make sense. America to me was like the land that had everything, all this opportunity, all these resources. So I did not understand it,” she stated.

PAIN AND SUFFERING OF OTHERS

Dr Rainford said she cannot take credit for being the first to start this conversation, because she learnt a lot from watching the pain and suffering of advocates such as Charles Johnson, the son of TV Judge Glenda Hatchet, whose wife Kira Johnson died in childbirth when she was getting care at what would normally be considered an excellent hospital.

“She died after having a routine caesarean infection. This is after he kept on asking for help over and over. And I remember him writing and saying he's been advocating for women because of her death,” she said.

She said Johnson was told his wife was just not a priority. And by the time they took his wife back to the operating room, she was dead within minutes – “It was too late”.

The other story that inspired her was Wanda Irving's daughter Shalon Irving, a double PhD, who had a caesarean section, went home fine, but kept having problems.

Irving, who was adequately resourced, went back to see her physician, was sent home and then the very last time she was seen, she got medication for high blood pressure and collapsed within hours. Irving went to the hospital but never recovered.

“And these are women who are bright, intelligent, well resourced, no limitations in terms of poverty. That wasn't their story. Before I wrote my book, some of the stories that brought it home to me really made me realise how big the problem was,” said Dr Rainford.

'Pregnant While Black' is targeting not just minorities, but caregivers, policymakers and the village.

“We need help. We need advocates, and the black community cannot do it on our own. We need people outside the black community to recognise the value of black women and help and recognise that we need equity and are deserving,” she stated.

She believes the solution is investment in maternal health, with direct investment in black maternal health; as well as programmes that have proven efficacious.

“For example, one strategy is making sure that black women have doula support, which has been shown to improve birth outcome for black women. Medicaid covers doula support in certain states,” she said.

According to her, 65 per cent of black women are insured by Medicaid for their pregnancy and postpartum care, so having access to prenatal care helps not only in the pregnancy, but in the postpartum and more states are increasing the postpartum coverage for one year.

“That is also something that can be helpful. And also, not just extending it, but the resources that are given to the places that take care of black woman need to increase,” said Dr Rainford.