Disabled students look overseas for higher education

He wants to join the ranks of the great journalists that Jamaica has produced but his lack of sight means he might never see that dream come true.

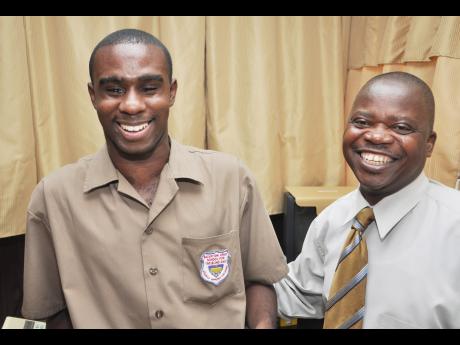

Andrew Gentles is the head boy at the Salvation Army School for the Blind and, while he has never travelled overseas, he speaks Oxford's English with a British accent he says he adopted through the many audio books he listens to out of the United Kingdom (UK).

While some may find his accent strange, Gentles, 21, embraces it. In fact, he fully embraces the British lifestyle and he is confident this will help him achieve his dream of becoming a journalist in the UK or in the United States, where he thinks opportunities are better.

"There are no opportunities for me as a blind person here. There is nothing really for me to do. I have a friend who finished CARIMAC at the University of the West Indies and still did not get into his desired job as a journalist. They wouldn't employ him," said Gentles.

keen on current affairs

Gentles is keen on current affairs. He harshly criticises government actions, and hopes to one day share his views on his own talk shows. Already, he has a list of topics which he guards. Many of the topics are dealing with local issues, however, Gentles plans to tie in a few international issues as well.

"This society does not have what it takes to accommodate blind people. They speak about legislation but we don't need legislation. We need the steps to be put in place to accommodate blind people day-to-day."

Youngsters like Gentles represent a growing stream of disabled students who are contributing to the brain drain of the country, argued at least two teachers of students with disabilities.

"Unemployment is only one part of the problem," said Erharuyi Tyeke, principal of the Salvation Army School for the Blind.

"There are many subjects that they have to do in order to gain employment in Jamaica and those subjects are normally limited to the sciences and mathematics. This has been a challenge to these persons.

"The subjects they do are limited to the humanities and a few in the social sciences. When they join that queue, many of them are not able to get a job," added Tyeke.

"We, in developing countries, don't have the resources to facilitate study in, especially, the sciences, so many disabled students opt to go overseas to pursue further serious studies."

local discrimination

According to Tyeke, the discrimination meted out to the blind locally does not help the situation.

Tamu Clayton, visual arts teacher and interpreter at the Lister Mair/Gilby School for the Deaf, said many of her students have migrated because there is little surety they will be properly accommodated at local colleges.

"The colleges here are not going to pay for interpreters because interpreters are expensive," argued Clayton.

She noted that there are students at her school who are willing to pay the tuition fees to enter the University of the West Indies (UWI) and the University of Technology (UTECH) but are deterred because of a lack of interpreters at the institutions.

"This is after they have survived the struggles of limited stationery and reading material to aid their learning at high school, said Clayton as she agreed with Tyeke, who bemoaned the problems facing blind students whose learning is stymied by a shortage of reading material and local texts in Braille.

"Many of them pass CXC exams with six subjects, eight subjects, but they can't get into college locally as there are no interpreters," said Clayton.

"If the Government sets up interpreters for the colleges everything would be fine, but many of them (deaf students) finish school here, and then they search and search trying to find colleges abroad that accept the deaf.

"When they leave, very few come back. So they learn here, get smarter abroad and then stay there," she said, explaining that such educated individuals could serve the country as interpreters or caregivers for other deaf and hard of hearing persons.

However, Dr Carroll Edwards, director of marketing and public relations at the UWI, explained that while the university has no official sign-language interpreter, measures are in place to assist three registered students who have declared that they are deaf and hard of hearing.

academic support unit

"The Office of Special Student Services provides note takers and recorders to assist deaf and hard of hearing students," said Edwards.

"There is also an instrument, phonic ear, which amplifies the sound for those who are able to benefit from this assistance. The academic support unit provides assistance for those with challenges in English and mathematics-based courses, and examinations are written in specialised areas."

Edwards said that the UWI has introduced a degree programme in sign language in its department of language, linguistics and philosophy. This aims at increasing the pool of professionals who are trained to address the needs of the deaf community."

Hector Wheeler, associate vice-president of advancement at UTech, provided a similar story when asked about its provisions for deaf students.

"I know that there is a special committee set up to look at how to better assist challenged students, but I don't know of any interpreter specifically for the deaf. I do know, though, that things are being done to assist the general disabled community. I'm just not sure if interpreters are a part of it," he said. Both universities, however, have made provisions for blind and wheelchair-bound students.