In the centre of a round table draped with a white piece of cloth was a bunch of white roses. Surrounding them were white unlit candles. Set next to that table was a very long, white section.

Small, white candles were placed along the edges. On it were bouquets of white and yellow chrysanthemums. It was not as elaborate as it could have been, for it was a different order: a celebration, not a feast. Tasteful simplicity was the theme.

It was the Revival table set for Edward Seaga, late former prime minister of Jamaica.

The Revival table is one of the sacred symbols of Revivalism and is constructed for various occasions. This one was to honour Seaga.

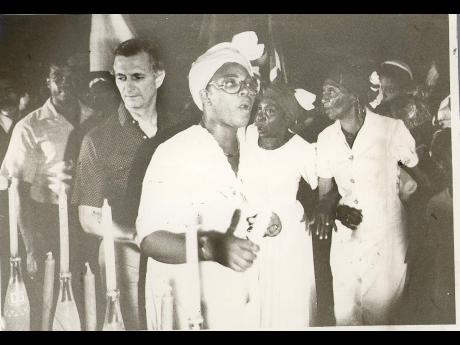

Upon the arrival of the Revival bans (bands) from all over Jamaica, people, mainly uniformed folk, gathered around it, bringing greetings, singing, and praying.

It is a grass-roots movement that is said to have originated in 1860-61. It is the religion of the people, the alternative to European religious sensibilities and worship, consisting of elements of Christianity imbued with African spirituality, which Seaga found fascinating, thus becoming a scholar of it. And in the storied space of Tivoli Gardens, there was a spiritual meeting around the table.

The tenor of the voices, the cadence of the notes, the repetition of the lines, the closing of the eyes, the looks on the faces were undoubtedly Revivalistic nuances. The celebrants know the alphabet of the Revival language and turned it into words. There were the sounds of self-determination and redemption and the sound of a belief in a “true and living God”.

FAMILY AFFAIR

And then the Seaga family arrived at the unlit table. Among them were two of his children, Andrew and Anabella, and their spouses, and children.

The candle-lighting started with them, others subsequently joining in. One by one, the candles were lit, illuminating the flowers.

The singing, dancing, and the music continued, and there was great joy.

West Kingston Member of Parliament Desmond McKenzie and Culture Minister Olivia Grange were part of the mix, and when the reality gripped them, they hugged and cried.

Minutes before midnight, the bishops, dressed in their regalia, rejoined the crowd. The instrumental music had died, and the voices are now the lead. They move around in a circle. A few females are among them. They are surrounded by other participants and onlookers. Around and around they go en masse as they hum and moan, uttering sounds that perhaps only they can understand.

The hands flailed and the legs trumped.

“Stand on the left, and stomp with the right,” a young man instructed another.

The circle got wider as they created a bigger space. There, the movements got vigorous and fervent. The energy, the sense of purpose, the sound of shoes striking the concrete were hypnotic. The mélange of sounds rose into the almost starless sky over the four corners of West Kingston, and beyond.

Affixed to the rail on the upper level, above each end of the table, there was a full image of a smiling Edward Seaga in a suit and tie. He seemed to be looking down on what was happening, and he seemed pleased. The Harvard graduate, who lived among the people and studied their ethos and religiosity, was being honoured with two tables full of candles and flowers. He was fascinated by them; they were touched by him. And there they were, singing, chanting, dancing, scatting, trumping and trampling for him.

CELEBRATION OF LIFE

In her brief address, Grange said, “Mr Seaga was not afraid to embrace Revivalism, and he was not afraid of all of you saints, and so tonight, we are not afraid to celebrate his life.”

And then the cheers, loud tolling of bells and alleluias responding in agreement.

Outside, in the square, the air was festive, and business was thriving. What was going on within was projected on a big sheet, and people watched the theatre that is the Revival table ritual. What were the narratives that were unfolding? What were the questions the celebrants were answering with their voices and movements? What were the messages they were sending with their music, their singing, their dancing, their turbans, and their uniforms?

And when the last note would have been struck and the celebrants had gone back from whence they had come, they would feel drained and tired, for it was a night when they chanted, scatted, trumped and trampled for the Lebanese-Jamaica man, the ‘One Don’, the former prime minister, finance minister, and minister of welfare and development, a man who McKenzie said “believed in all of us, who respected our views, who accepted us for who we are”.

“In life and in death, Edward Seaga belong to us, and we belong to him,” McKenzie declared, soon after which he led the gathering into two of Seaga’s favourite songs, I Must Have The Saviour With Me and A Nuh One a Dem.

On the night of Wednesday, June 19, ‘a nuh one a dem’ came out, but a throng of people from all social strata to gather around the Revival table laid in honour of Edward Phillip George Seaga.