Playing our part to achieve racial equity and justice: PART 1

The PJ Patterson Centre for African-Caribbean Advocacy seized the opportunity on September 24 to remind the world of unfinished business as it relates to racial equity and justice, by hosting a webinar to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Third UN Conference against racism held in Durban, South Africa, which produced the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action (DDPA).

The webinar had the support of the Centre for Reparation Research and the ministers on Durban.

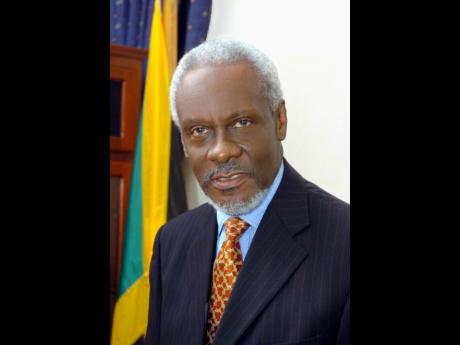

Below are excerpts from Mr PJ Patterson’s speech.

Over the past two years the world has been rocked by the unrelenting and devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. In a time of information flow, we have been gripped by the troubling stories of families, communities and countries being ravaged by the virus. Two years into this pandemic we remain constantly distressed by the ever-increasing numbers of lives lost and increasing infection rates.

What is even more troubling is the stark racial and social inequalities inhibiting access to healthcare. This pandemic has starkly revealed the interconnection between race, racism, economic inequality and health.

As noted by Oxfam in their report, the Inequality Virus, this has had far-reaching negative repercussions on vulnerable communities of racial minorities due to the systemic racism that already exists in certain states with majority communities of “Black people, Afro-descendants, Indigenous Peoples and other racialised groups more likely to contract COVID- 19, and to suffer the worst consequences. From access to healthcare, exposure to the virus related to occupation, to socio-economic status, non-white people have been made more vulnerable, thanks to inequalities built into the very structures of society.” (Futshane, Oxfam International, 2021).

As our centre predicted in its very first public release, the dynamics of global power have prevented equitable distribution of the vaccines between developed countries and vulnerable developing countries. This division and inequality throughout our global society has made the relevance of the DDPA even more significant.

We, who were leaders in Durban, have now become elders who can engage in a critical reflection on the impact of this solemn declaration.

What has Durban achieved in its stated objectives of addressing race and racial discrimination in the last 20 years? Specifically, we must assess whether the declaration adequately addresses the impact of racism and racial discrimination, as well as the legacies of slavery and colonialism which have entrenched the global inequalities that have become even more pronounced in today’s global pandemic.

There are those who occupy pivotal positions of leadership in many developed nations and international institutions that deliberately seek to disregard any truthful answers and dare to treat any such conversation as impolite or otiose.

The present leaders in Africa and the Caribbean, availing themselves of the scholarship, research, and skills in our universities and the work of centres and institutes such as this, cannot be lulled into silence and inactivity.

That we will never forgive nor forget.

We of the developing nations must realise that our modern-day identity and capacity to build and develop continue to be defined by the vestiges of our colonial past. Our identity remains linked to the injustices and violations experienced by our ancestors. We are a global diaspora that remains afflicted by the legacies of slavery and colonialism.

In a global community in which racism, racial discrimination, intolerance, and xenophobia remain ever present, the concerns for minority communities, we must ask what more must be done to move our international community forward towards tolerance, equality, respect and racial justice.

MEANINGFUL CONSENSUS

We recall that the Durban Conference in 2001 was intended to engage nation states in a diplomatic forum that would address the pervasive issues of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and intolerance that permeated our global society.

We examined the manner in which state institutions address concerns of racism in health, education, laws, social policies, state economics, and regulations, in response to the historical legacies of slavery, colonialism, and religious discrimination.

The Durban Conference, and the subsequent declaration, was intended to provide a road map for states to appropriately address these significant and critical concerns.

Integral to the spirit of the conference was the hope that as a community we could come to meaningful consensus that would admit the wrongs of the past, and the ongoing injustice and human rights violations. We were seeking to provide a way forward to ensure that previous crimes against humanity and human rights violations based on race or colour are never repeated.

Billed as the 3rd International Race Conference, it was designed to facilitate significant dialogue on the problematic past and relationship underscored by racism and discrimination between the Global North and South.

With the adoption of the declaration, we formally accepted a comprehensive set of strategies that directly targeted race, racial discrimination, intolerance and xenophobia. It encouraged states to implement anti-discrimination laws and called for the strengthening of legal protection for racial minority groups, refugees, and indigenous people against all forms of abuse and discrimination (Petrova, 2009).

It also called on states that adopted the declaration to create programmes and public education strategies that examined the causes of racism and racial discrimination in an effort to eliminate racism throughout our international society.

At the heart of the DDPA was the need to directly provide recourse to legal support for minorities affected by racial injustice and discrimination and to stymie the further proliferation of racism by educating the public and providing state intervention for tools. It sought to specifically highlight for nation states that instances of inequality, underdevelopment and lacking institutional capacity for growth are in fact directly related to pervasive elements of racism which have been interwoven into most, if not all, aspects of state and society.

The discriminatory policing practices of some states that continuously target black and ethnic communities, the legacies of racism have been so intricately developed to continue the marginalisation and discrimination of minorities – thus further entrenching systems of oppression in these communities.

For many former colonial states (with large Afro-descendant communities) attending the conference it was also imperative that the DDPA formally acknowledge slavery, the transatlantic slave trade and apartheid as human rights violations.

We decided that the necessary avenues for restorative justice be put in place to address the legacies and impact of these institutions on the African diaspora. It was critical that these systems be recognised formally for carrying out and profiting from human rights violations against a large group of people.

CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY

The Caribbean delegations posited that slavery and the slave trade were in fact crimes against humanity.

Our demand was denied.

We find that though its intended goal was to address the racism and racial discrimination, there has instead been a widening of the divide between the Global North and South.

Discussions on finding a way to move forward in relations ultimately broke down due to an unwillingness to acknowledge and make appropriate amends for the role played by the north in establishing and employing these systems of racial discrimination and prejudice.

With 31 states refusing to return to the table, there is no universal consensus on how to adequately address racism and racial discrimination in our global community. Racially marginalised states are once again placed in a position of powerlessness and under-representation due to the deafness of more powerful players.

Without global commitment and consensus, we lack the power to effect critical change and eradicate racism and racial discrimination for future generations.

In response to this, many of us have sought independent recourse for the atrocities of the past. There is CARICOM’s 10-point Plan for Reparatory Justice which not only demands a formal apology from European governments for the atrocities of slavery and colonialism, but also insists that they take more responsibility in building capacity in countries that were ravaged by these systems.

Over the past 20 years the international community has experienced significant seismic shifts in the manner in which we operate as a collective of states; how we view each other as global neighbours; and how we respond to injustice and instances of inequality targeting the marginalised many.

For many black and Afro-descendant communities plagued by the legacy of slavery and colonialism (such as social inequalities and continuous economic hardships), the idea of racial and social justice at times appears to be distant and unattainable goals.

During the last five years we have seen a growing awareness of institutional forms of racism, prejudice and xenophobia. We have seen communities of the young across the world stand up and demand better from their governments, civil society, educational institutions and even from their peers who refuse to take proactive measures to eliminate these forms of social and racial injustice.

We have seen racial activism and social justice movements galvanise communities demanding change, and recognition of the past so that they can ensure an equitable future for the most marginalised.

In the shadow of Durban, a dualistic response to race in the global community ignited a new era in race relations and racism. With proliferating white supremacy factions and anti-migrant and refugee rallies in many countries, there are as many counter-protests.

A CRITICAL MOVE FORWARD

The emergence of Black Lives Matter and movements protesting the abuses suffered by indigenous peoples in the global north highlight a critical move forward led by our youth, to address systems of institutional and systemic racism and racial discrimination in our international society.

The core objectives of the Durban Declaration remain relevant today. Its more lasting legacy is that it formally recognises racism, racial inequality, discrimination, intolerance, and xenophobia as facilitators of the social and economic issues affecting marginalised groups.

The POA aligns strategically with the Sustainable Development Goals, in that it recognises that racism and racial discrimination and inequalities do in fact foster socio-economic disparities in communities of African descent. With racism being entrenched in certain systems of governance, eradicating poverty, unequal access to healthcare and education as well as concerns related to gender is notably more difficult and more complex to disentangle from the state infrastructure.

It is critical that states address these issues related to systemic racism and discrimination head-on in order to eradicate poverty and improve access to healthcare.

The DDPA, noting the connection between race, racism and economic disparity and poverty, has been integral in the development of the Sustainable Development Goals. This in turn allowed governments, the civil society, and other actors to comprehensively address the barriers to wealth, development and sustainability through the lens of race. We have to tailor the needs for economic growth and poverty alleviation of these marginalised groups in a more direct way, eliminating all discriminatory practices that would hinder their growth.

As we grapple with racial and economic disparities emphasised by the global pandemic, the POA highlights that it is imperative for nation states, through international cooperation, to increase investment in healthcare systems, public health, drinking water and environmental control in communities of African descent.

These are the communities that are left bereft of the adequate infrastructure to safeguard itself in times of health crises. There is need for more targeted support in these areas to facilitate their movement towards development and growth.

TAKE RESPONSIBILITY

As the COVID-19 pandemic has moved into the stage of curtailing the virus through a global vaccination initiative, considering the racial undertones of access to the vaccine must be brought to the fore as we discuss the DDPA. The World Health Organization (WHO) has rightly deplored the delay of wealthy states in the Global North to share their supplies of the vaccine with poorer nations, we are witnessing a “vaccine apartheid”.

As some Western countries are now administering booster shots to their citizens, many African and Caribbean nations are still left trying to source suitable access to this life-saving vaccine for their people.

The DDPA is still supported by nation states who view the eradication of racism as a critical measure of moving our global community forward and addressing the wrongs of the past. Yet, more needs to be done.

We need a global support on this initiative, which includes re-engaging the most powerful nations in this dialogue. It relies with us all to take responsibility and acknowledge our respective roles the propagation requires of this pandemic of racial hate and discrimination.

PJ Patterson is a former Prime Minister of Jamaica and president of the PJ Patterson Centre for African-Caribbean Advocacy. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com