Speaking truth, defending credibility, advancing democracy – Pt II

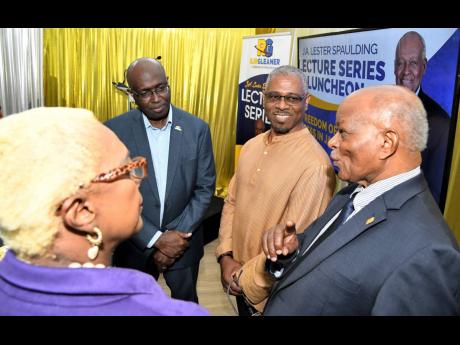

The following is the second part of excerpts from the presentation made by Patrick Prendergast, campus director, The University of the West Indies – Western Jamaica campus, during the RJRGLEANER Communications Group’s Inaugural J.A. Lester Spaulding Lecture, held on World Press Freedom Day, May 3, at Studio One, Broadcasting House in St Andrew.

It is interesting that the theme for WPF Day 2023 speaks to shaping a future of rights! My question is, are we prepared to be a rights-based media? This raises important questions – if not a dilemma – around both the regularly spoken of and the rarely spoken of rights, not just for the public but also for the journalists and reporters. For example, we do not talk a lot these days about the rights of journalists and media organisations not to reveal their sources, to launch ‘sting’ operations, and to be free from government interference; but, there is a lot of talk about media not doing enough investigative journalism.

Paradoxically, when some serious investigative work is done people get agitated, especially – and as it should be – in high places, in the rooms and halls of power. We need to find out who are the sources of the leak!

As Rowan Cruft in a December 2021 article in the Journal of Applied Philosophy, entitled ‘Journalism and Press Freedom as Human Rights’, contends:

‘‘The rights of journalists (however qualified) to protect their sources are normally justified by the interests of journalists in being able to collect information. But that interest is deemed to be worth protecting because it serves the public. That is, the journalist’s interest is valued because of its usefulness to members of the public at large.’’ (Cruft, 2021 quoting Raz, 1994)

“It is ultimately for the good of the public that we hold moral duties not to force journalists to reveal their sources, rather than primarily for the good of the individual journalist. Legal duties operationalise these moral duties whose grounds are not the good of the individual journalist. Such duties (both moral and legal) seem to constitute role-based rights for journalists, and their non-individualistic ground (in the good of parties other than the journalist) seems to make them sharply distinct from human rights on the naturalistic view.”

Again, I throw this question from Cruft into the lap of our media workers and students as an area for interrogation: What is the relation between journalists’ role-based rights and human rights?

Clearly, I agree with Cruft that:

“The rights of journalists to engage in communication are … not rights that they hold for their own sake … Like many roles, journalism is defined by constitutive norms – norms that explain the role’s point, purpose, and limits. If one’s behaviour is governed by these norms (in some difficult-to-specify sense of ‘govern’), then one is a journalist – even if, as a bad journalist, one regularly violates the norms.

The human right to journalism and press freedom, Cruft argues, is a right that one’s society allows and enables some people to engage in the practice constituted in bringing truth that is of public interest to an open and public audience, and in fulfilling a moral obligation, obtains that truth by means not allowed to ‘ordinary citizens’. Such person must not only be recognised as having special rights but should also be guaranteed certain protections including their moral obligation to protect their sources. That guarantee and privilege also comes with an awesome set of responsibilities for all involved in making the news, so to speak!

The legacy of Lester Spaulding requires that media workers remain vigilant in not only advancing the rights of the public but in advancing their legal and moral obligations to pursue truth.

Media freedom as support to the development of an independent society

There was a course at CARIMAC that was about the history of the contemporary press, From Printing Press to Podcast! This was before IG or snapshot or any of the popular quick newsfeeds on social media.

In Jamaica, we could speak of the history of the press from the Jamaica Courant in the early 18th century to The Gleaner of the early 19th century. The survival of The Gleaner over its more than couple centuries of existence is the story of print journalism in Jamaica. Apart from the local community based papers – the most popular and consistent of which is the Western Mirror, itself doing some 42 years (est. October 1980) – only a few national attempts have survived for any extended period.

The Jamaica Observer is this year celebrating 30 years (est. March 1993); but some of the well-known newspapers that have failed to stay the journey include, Public Opinion, The Daily News, and The Jamaica Record.

Understandably, while radio broadcasting does not enjoy the long history of newspaper, its growth in Jamaica is phenomenal. This is a 20th century story; but generally, information communication technologies are probably the most rapidly changing and expanding new age technologies globally.

From John Grinan’s ham radio and the call sign VP5PZ, public broadcasting began in late 1939. By 1940 the station became known as ZQI and ran for a decade before the government allowed for private company to provide broadcasting services in 1949. That was the birth of the Jamaica Broadcasting Company, which, it must be noted, was a subsidiary of the London-based Re-diffusion Group. However, in 1950 ZQI was taken over by the JBC and commercial broadcasting began under the call sign, Radio Jamaica and the Re-diffusion Network. RJR cometh! And so too did the community gathering posts for listening to broadcasts.

I mention this because, community gatherings have always been a concrete manifestation of the transforming ICTs in our country. Importantly, they were also an integral part of the information and education of the Jamaican people and society. Commercial radio and public service radio, though, would always be in contention – and as I have argued in my work in community media, genuine public service media cannot survive without subsidies in the same way commercial radio cannot survive without advertising. No matter the technology, it costs! The answer was always to be found in popularising the content – making it local and relatable to the audiences, wherever they are through radio dramas, local music programmes, etc.

Of course, by 1959 the government decided to enter the broadcasting arena. JBC cometh. Norman Manley, the premier then, wanted to have in Jamaica what other national broadcasters such as the BBC were doing. The development of local content – drama, music, voice – and national development information and education took on new impetus and a full-scale diversification of broadcasting content had begun.

The growth of media platforms available also expanded with the introduction of television in August 1963 – on the first anniversary of independent Jamaica, and truly, the story of Independent Jamaica would also become the story of independent media. The shift from foreign ownership and content to local ownership and content and, of course, the growing debates and tension between the role of private, commercialised and public developmental media, and the role of journalists, reporters and media workers in serving private interest or shaping the nation.

All of this push and pull between State, private and public imperatives was always layered on top of the transforming technologies and how these new technologies could be used in transforming our people – politically, socially, culturally. The informational and educational value – what I call, the instructional and directional value of media – was always of primary concern. So it was in the early development of media. So it remained over the centuries, and particularly over the decades of our independence. So it is today.

Dr Patrick Prendergast is campus director of the UWI Mona – Western Jamaica campus in Montego Bay and a senior lecturer in development communication.