Why we should embrace CCJ

A final court is a most critical national institution because of the unique role it plays in our democracy.

The interpretation that a final court of appeal gives to a Constitution often has far-reaching effects on the people of a country. It can change people's lives for better or worse.

Unlike courts at other levels of the system, a final court is not bound by its own decisions. In the most significant cases that final courts must decide, they are required to chart new ground in answering questions that have not previously been determined, and in doing so, they cannot merely apply settled law to the facts of the case before them.

Difficult cases, especially those arising under the Constitution, are determined by the judges of the final court applying broad principles of justice that are ultimately rooted in the socio-political philosophy and contemporary morality embraced by those judges.

For example, in a series of cases beginning with Pratt v Morgan in 1987, the Privy Council has effectively emasculated the law in Jamaica that imposes the death penalty on persons convicted of murder. Similarly, the final courts of independent countries have transformed their societies by far-reaching decisions on a range of social and political issues, including segregation, abortions and same-sex relations, even deciding the outcome of a US presidential election.

In Jamaica, since the advent of the Charter of Rights in 2011, perhaps the most poignant questions relate to the efficacy of the charter's savings provision, which was deliberately adopted by Jamaican legislators to protect the buggery law, and the law prohibiting abortion, from being challenged under the Charter of Rights. Those two laws are both found in the Offences Against the Person Act, a Victorian statute dating from the 1860s.

Challenges Loom

It is likely that court challenges to those archaic laws, and to the savings clause that seeks to protect them, will, sooner or later, be brought under the Charter of Rights. Similarly, the charter's definition of marriage as a legal union between one man and one woman, the inclusion of which was also intentional, may also come to be tested in the courts.

These three issues stand out as candidates for human rights-based litigation because they are each strikingly inconsistent with the conception of human rights that has prevailed in contemporary Western society.

These observations are not vapid or contrived fearmongering. To the contrary, these are very real and relevant considerations in the debate on whether or not to stay with the Privy Council.

It offends our sense of nationhood and is inconsistent with our national independence, for these important constitutional questions to be decided for the Jamaican people by British judges in the UK Privy Council, whose world view is informed by the social norms and ideologies that are very different to our own.

Would the people of the United States accept their final court's recent ruling that legalised same-sex marriage if the judges were foreigners? Clearly not. Are the Jamaican people any different, any less, in this regard?

More than 50 years after gaining independence, no self-respecting country should continue to cling to the court of its former colonial master, manned by judges who spring from that foreign society, as the final arbiter of its Constitution and the laws enacted by its elected Parliament.

Jamaican Self-doubt

While some commentators may draw comfort from the detached separateness of the UK Privy Council, such comfort is based on a fundamental self-doubt. I accept the principle that these questions should be decided by judges who share a common identity, culture, ethical standards and morality with the very people who will be impacted by their decisions.

I am comfortable with the CCJ becoming our final court and deciding these types of questions because Jamaica has been an integral participant in the establishment, design and financing of the CCJ, and its jurisprudence has been of the highest quality over the decade of its existence.

Jamaica is not in a position at this time to establish a local final court that would pass the acid tests of financial independence and structural protection from political interference, and the CCJ already meets these critical objectives.

I wish to state for the record that I would not presume to predict the outcome of a case brought before our final court to decide these questions, whether it be the UK Privy Council or the CCJ. Any such prediction would be inappropriate and unwise. However, whatever the outcome when these questions come to be determined by our final court, and whatever my personal beliefs on these matters, I am firmly of the view that they should not be decided for the Jamaican people by the UK Privy Council.

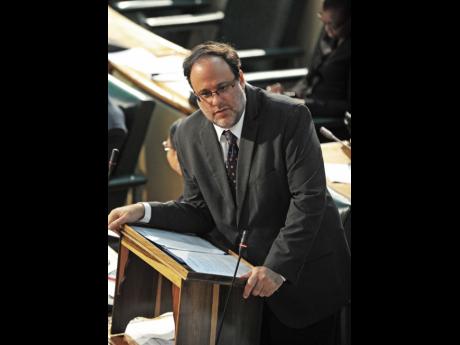

- Mark Golding is an attorney-at-law and minister of justice. Email feedback to columns@gleanerjm.com and mark.golding@moj.gov.jm.