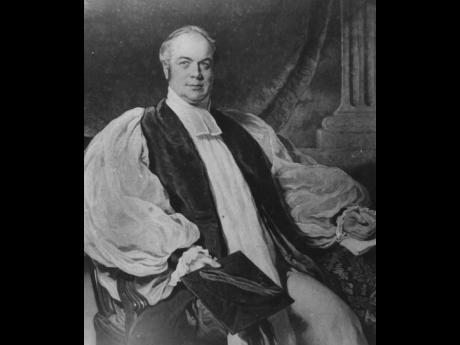

Christopher Lipscomb’s enduring legacy

In the early 19th century, the British Government had to select a suitable candidate for the position of Bishop of Jamaica. The Diocese included The Bahamas and the Bay Islands of Honduras. Their first choice was the Reverend Charles Richard Sumner, who served as Chaplain to King George III. However, much to the surprise of many, Sumner turned down the offer of the Jamaica See, citing family reasons.

Considering Sumner’s refusal, the attention turned to another candidate, Mr Lipscomb, whose “neutral” stance within the Church was seen as a favourable quality.

It was on July 24, 1824, when Christopher Lipscomb stood before the majestic walls of Lambeth Palace, ready to be officially consecrated as the Bishop of Jamaica. The ceremony itself was a solemn and grand affair, with the archbishop, he Most Rev. Charles Manners-Sutton, leading the prayers and anointing Lipscomb with oil. After the final blessing was given, Lipscomb knelt before the archbishop, who placed a symbolic staff in his hands, signifying his authority as the new bishop. The weight of the staff felt heavy and unfamiliar, but Lipscomb knew that he had been chosen for this task for a reason.

And so, as the bells tolled in the distance, the word was out that Lipscomb had indeed been chosen for the post, marking the end of a chapter in the Government’s search for a worthy candidate to lead the Church in Jamaica.

SUGAR-COATED WORDS

When Bishop Lipscomb arrived in Jamaica on February 11, 1825, he was greeted with sugar-coated words of welcome from the establishment, but he soon realised that his task would not be an easy one. The hard-nosed assemblymen in Spanish Town were determined to control him, and they made it clear that they expected his silence on the issue of abolition in return for their toleration.

Despite the challenges he faced, Bishop Lipscomb was determined to forge a diocese and establish rules for the unruly clergy in Jamaica. With his handpicked group of clergymen, including his brother-in-law, Archdeacon Edward Pope, and his brother, Henry Lipscomb, by his side, Bishop Lipscomb set out to bring order to the chaos that had long reigned in the Jamaican Church.

As he navigated the treacherous waters of Jamaican politics, Lipscomb was immediately thrust into the island’s political turmoil. The rising tensions between the slave population and the declining sugar economy posed a significant challenge for the inexperienced priest.

Bishop Lipscomb found an unexpected ally in the Minister for War and the Colonies, Lord Bathurst, and the Duke of Manchester, the Governor of Jamaica. Together, they negotiated ameliorative measures for the slave population, much to the dismay of the hardline pro-slavery members of the Assembly.

It seemed that even his own clergy, who should have been his pillars of support, had abandoned him. The local Jamaican clergy, under the loose control of the Bishop of London, had become complacent and resistant to change. Many of them had fallen into the trap of “creole habits,” embracing the lifestyle of the white minority rather than focusing on their sacred duties.

GLIMMER OF HOPE

But amid the chaos and disillusionment, there was a glimmer of hope. The young Irishman, the Reverend John McCammon Trew, had taken it upon himself to lead by example in the parish of St Thomas-in-the-East. His dynamic and passionate leadership had resulted in the opening of two new chapels, providing much-needed spiritual guidance to the scattered slave population across the island.

In 1825, the bishop was hard at work confirming a record number of candidates into the Anglican Church. Among the 786 individuals were 106 whites, but the majority were coloured and black, reflecting the diverse population of the island.

As the bishop travelled to Spanish Town and St Ann in October of that year, he was struck by the enthusiasm of the free coloureds who were eager to join the Anglican catechists. These individuals were trained to provide religious instruction to the slave population in the interior, a noble task that the bishop had long championed.

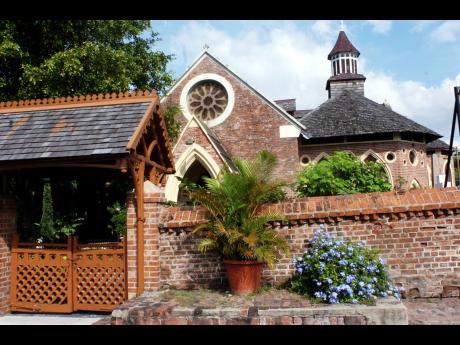

In an October 8, 1826, correspondence to the Earl of Bathurst, the bishop informed him of the “recent consecration of three new chapels in Jamaica, each a testament to the dedication and generosity of the local community – Harewoods’ Chapel, situated in St Thomas in the Vale? The others lie “in the remote districts of Carpenter’s Mountains and Mile End Gulley in Manchester, St David’s and St George’s Chapels ….”

Despite facing prejudice and discrimination, the free coloureds did not waver in their commitment to spreading the teachings of the Church. They founded schools for coloured children and enslaved individuals, taking it upon themselves to educate, teaching not only catechism but also reading, writing, and arithmetic and uplifting their communities. By 1835, there were 56 clergy and 95 lay teachers. In response to a circular from the Home Government that was sent to all religious organisations in Jamaica, Bishop Lipscomb reported that “ there were 142 schools, where instruction was given to 8,500 scholars … .” (J.B. Ellis).

By 1839, education was flourishing like never before. The appointment of a general clerical inspector of elementary (Church) schools marked a turning point in the growth of knowledge and learning.

For nearly 19 years, Dr Lipscomb served the Church. But tragedy struck on the fateful day of April 4, 1843. During his labours, Dr Lipscomb passed away suddenly, leaving behind a legacy of dedication and passion for education. Dr Lipscomb was laid to rest in the churchyard of St Andrew’s parish church.