The taunting, tormenting, and trial of William Knibb et al

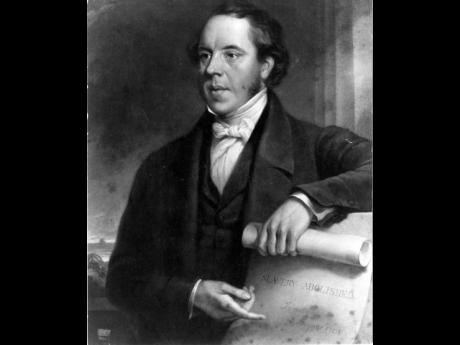

THE BAPTIST William Knibb arrived in Jamaica from England in 1825 at a time when missionaries were strongly advised not to interfere with the status quo. Civil and political matters were not their business. He had come as a teacher to Kingston to replace his deceased brother, Thomas.

Knibb was not initially a preacher, but when his abilities were noticed, he was encouraged by established missionaries to preach. Yet, he was not trained, nor was he licensed. Subsequently, he was permitted by the Baptist Missionary Society (BMS) in England. At the time he was stationed at the Baptist Mission House along East Queen Street in Kingston.

Knibb left the teaching job there to do missionary work at Ridgeland near Savanna-la-Mar in Westmoreland. That was where he met Sam Swiney, the deacon who was convicted, flogged and treadmilled for preaching without a licence, when in fact he was only praying. Knibb reported the matter to the BMS, and appealled the conviction and punishment to the secretary of state for the colonies. After two years of investigation the magistrates were dismissed and recalled to England. Knibb had effectively become the enemy of the plantocracy.

When the Sam Sharpe Rebellion erupted in western Jamaica on December 27, 1831, Knibb, like most of his associates and the planters were caught off guard. Blame was immediately placed on the antislavery missionaries. Martial law was declared on Saturday, December 31 when Knibb and other missionaries were in Falmouth. They became jittery when they saw rebels being taken to jail.

The following day, Knibb held two prayer meetings at his chapel. But, whatever Knibb prayed for was not what he got, it seemed. For, after the second meeting, an officer named Denoon, accompanied by armed soldiers, seized Knibb and three other missionaries – William Whitehorne, Samuel Nichols and Thomas Abbott. While Whitehorne and Nichols were escorted to the Guard House, Knibb and Abbott were told to present themselves there.

At the Guard House the four missionaries waited to see Lieutenant Colonel Cadien, but they instead saw Major Robert Neilson who asked them to report back every morning at 11 until orders were received from the commander-in-chief, Major General Sir Willoughby Cotton. The missionaries returned to their family thankful that nothing serious had happened, but something very serious was to come. The following day they finally met Cadien who ordered them to join the militia.

They, being missionaries of the gospel, were shocked, but Cadien could not have cared less. Abbott joined the artillery company. Knibb joined the Fourth Company. Whitehorne was more concerned about being called captain. Nichols fell ill and was given permission to return to St Ann’s Bay. Knibb and Abbott were sent on guard duty. Abbott spent the night pacing as a sentry. Knibb, too, fell ill and was sent home.

On Tuesday, January 3, Knibb and Abbott wrote a letter to the governor asking for exemption from military service. Cadien got hold of the letter before it was sent off to Spanish Town, and promised to give them a feedback before noon. While they were waiting anxiously, suddenly Captain Paul Doig of the Sixth Battalion Company, accompanied by two armed soldiers, burst into the room and pointed his sword threateningly at Knibb.

In an angry voice Doig ordered that Knibb be arrested. Before he was taken to the ballroom upstairs the courthouse, which was being used as a barrack, Knibb was paraded and humiliated. Abbott, too, was brought to the barrack. When Whitehorne heard what had happened to Knibb and Abbott he headed for the barrack, but he too was detained by the sentry. They were then told that Cadien had got permission to send them to the headquarters in Montego Bay.

At 11:30 a.m., they were marched through the streets of Falmouth under a military guard to a wharf. A large and boisterous crowd followed them. At minutes to 12 they left by canoe for Montego Bay. After travelling under a boiling sun for seven hours they reached Montego Bay where they were taken to the courthouse, then to General Cotton’s lodgings, then to Custos Barrett’s house, and back to the courthouse, carrying their luggage all the way where they were taunted by passersby.

They were accused of causing the insurrection by preaching to the enslaved about freedom. In the packed courthouse, the ailing Knibb was the subject of much ridicule, invective, and threat to his life. Having nowhere to go, they were detained in the jury box. By chance, a friend of Whitehorne, a Mr Roby, the collector of Her Majesty’s Customs, brought them to the Custom House for the night. He eventually secured conditional bail and a place for them to stay, and did all he could to protect them from mobs and the planters.

While Knibb was awaiting trial, he visited Falmouth and saw his chapel in ruins. His presence inspired a mob that stoned the house in which he was staying for three consecutive nights. He was protected by enslaved and coloured people. Subsequently, the case against him was dropped, and he was once again a free man. The cases of Abbott, Nichols and Whitehorne also fizzled to nothing.